This is an adapted version of one of my university essays which looks at the setting of London in relation to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. Let me know if you have any favourite novels set in Victorian London!

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) and Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend (1865), tap into concerns prevalent in late nineteenth-century novels: anxieties surrounding the globalisation and urban expansion of Victorian London. Both novels emphasise the fears of the spread of the corrupting influence of the Orient (the East) into London (the Occident or the West). Charles Booth’s influential mapping of London in his Inquiry into Life and Labour in London (1886-1903) reinforces this viewpoint, likening the occupants of London’s East End to “savages”. Through the imperial discourse of the “savage” and the zoning of East and West London in Our Mutual Friend and The Picture of Dorian Gray, this works to portray London’s East as barbaric and ‘other’. Consequently, this works to reinforce anxieties surrounding the threat of the Orient to British society.

Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray reinforces Victorian London’s preoccupation with the zoning of London and the characteristic behaviour of the occupants within them, with “illicit measures located within the East; [and] social elegance in the West” (Dryden 126). The fluidity in which Dorian moves between his debauchery amongst the docks and opium dens of the East End to the high society of West London, emphasises his duality. Whilst Dorian’s travels between East and West London pose a threat to the society of West London, what is shown to be most damaging about the East is that it results in a loss of identity, creating an ‘othering’ of the self.

Despite the anxieties about the East End of London and the threat this poses to bourgeois society, Dorian’s status as a flâneur (someone who wanders around observing society), taps into the sense of allure that surrounds the East End as a place of “nefarious pleasures” (Dryden 49). The East End provides a space where the male bourgeoisie can break away from the rigid morality of Victorian society, highlighted by Dorian’s sordid delight in observing “the coarse brawl” and “the crude violence of disordered life” (DG 178). The scholar Paul Newland argues that the novel “imagines the East End as a decadent playground- a space in which exotic middle class fantasies can be played out” (84). Newland extends this point further to state that Wilde’s zoning of the East End as a sordid “other” space for hedonistic indulgences, is represented “as if it were a troublesome far-off dominion of the Empire” (85).

This imperial discourse of the East End as troublesome and savage, is prominent in Wilde’s descriptions of the occupants Dorian encounters on his venture to the opium den, such as “a half-caste in a ragged turban” (180). Wilde’s grotesque portrayal of these characters as barbaric draws upon “the descriptions of ‘savages’ in the fiction of Empire by writers like Rider Haggard […] [which] fuelled a perception of the East End as an urban jungle” (Dryden 48). In a period which witnessed the murders of Jack the Ripper, the idea of the “urban jungle” would have been familiar to Victorian readers. Indeed, Wilde draws upon these anxieties, highlighted through his descriptions of the labyrinthine streets of the East End, and Dorian’s near death at the hands of James Vane. Through Wilde’s constant emphasis on the animalistic natures of the population of the East End, it can be argued that this is a microcosmic representation of Britain’s larger empirical anxieties about the threat of the Orient to British morality.

The distinctions between West and East London in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend are not as rigidly defined as in The Picture of Dorian Gray; however there is still a sense that the East End is ‘othered’ from the rest of London. Scholars, such as Paul Newland, argue that Dickens’s descriptions of the difficulties Eugene Wrayburn and Mortimer Lightwood face in finding the East London dwelling of the Hexam’s “draws on the Judaeo-Christian concept of Hell” (54). This threatening aspect of the East End is reinforced by Dickens’s predatory portrayal of the characters who live there, highlighted by the description of Gaffer Hexam as “half savage” (13), and “a hook-nosed man […] [who] bore a certain likeness to a roused bird of prey” (OMF14). This hybrid imagery of eagle and man is unsettling, and similarly to Wilde, reinforces the barbarism of the “accumulated scum of humanity” that reside there, highlighting wider concerns surrounding the corruption of West London by the savage East End (30). Dickens ultimately depicts the East End as incompatible with human life: characters who live in it either have to move away (such as Lizzie and Charley Hexam), or in the case of Gaffer Hexam and Rogue Riderhood, are destroyed by it.

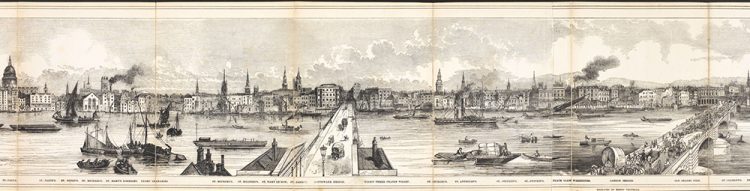

The River Thames forms a dominant part of Dickens’s novel and acts as a connecting force between characters across the city. Michelle Allen argues that this provides characters with “a means of mobility”; however, in Our Mutual Friend the Thames is a threatening presence, reinforcing Victorian fears regarding the loss of British national identity through its transportation of Oriental commodities (91). The abundance of eastern commodities in the Veneering’s home, and the ease with which these items are absorbed into it, illustrated through the references to the “caravan of camels take charge of the fruits and flowers and candles” (21), and the “ottomans” (125), dehumanises the Veneering’s until they become mere commodities themselves. If this small scale example is applied to a national level, it reflects the Victorian concern that this subtle colonisation of the British citizen through Oriental commodities could pose a threat to the dominance of the British Empire. This fear about the loss of British national identity from the East, is a primary concern of the novel, highlighted by the repeated references to Edward Gibbons’s book that Wegg reads to Boffin: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Both The Picture of Dorian Gray and Our Mutual Friend, address empirical concerns regarding the corrupting influence of the Orient on the British Empire. Whilst the threat of the East in The Picture of Dorian Gray is concerned with the damaging influence of the barbaric East Enders on West London society, in Our Mutual Friend it is the loss of national identity through the prevalence of these Eastern commodities that concerns the novel. It is the othering of the East End of London through imperial discourse, that Dickens and Wilde use to reinforce these anxieties about the threats the ‘savage’ Orient posed to British morality.

Works Cited:

Allen, Michelle. Cleansing the City: Sanitary Geographies in Victorian London. Athens: Ohio UP, 2008. Print.

“Charles Booth Online Archive.” Charles Booth Online Archive. N.p.,n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2015.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. London: Penguin, 1997. Print.

Dryden, Linda. The Modern Gothic and Literary Doubles: Stevenson, Wilde and Wells. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Print.

Newland, Paul. The Cultural Construction of London’s East End: Urban Iconography, Modernity and the Spatialisation of Englishness. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. London: Penguin, 2003. Print.

One thought on “The Setting of London in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens”