From coded manuscripts to commissioned texts, a new book shines a spotlight on the overlooked works of early medieval women writers.

Marie de France, Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich feature prominently in accounts of medieval women’s writing, but when did English women’s writing begin? This was a question that intrigued Diane Watt when she was working on her book Medieval Women’s Writing: Works by and for Women in England, 1100 – 1500 (Polity, 2007). While most accounts of women’s literary history usually start in the later Middle Ages, few looked earlier than the 12th century. ‘As I was working on Medieval Women’s Writing, I became increasingly aware of a pre-history, and I wanted to address this gap,’ Watt, Professor of Medieval English Literature at the University of Surrey says.

Her latest book Women, Writing and Religion in England and Beyond, 650 – 1100 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), uncovers this lost period of literary history, a time that saw the emergence of the first women-authored texts. One of the key writers from this era was Leoba, an eighth-century English missionary and abbess of Tauberbischofsheim (located in central modern-day Germany). Leoba was a supporter of Saint Boniface, a missionary who is credited with bringing Christianity to Germany. In the early 730s, she wrote a letter introducing herself to him, and included some lines of verse – the earliest surviving example of poetry by an English woman. ‘She clearly included her poetry as a way of showing her credentials, to show Boniface that she was a learned, capable young woman,’ Watt explains. Leoba’s letter seemed to have worked, as Boniface invited her to travel to Germany to join his mission.

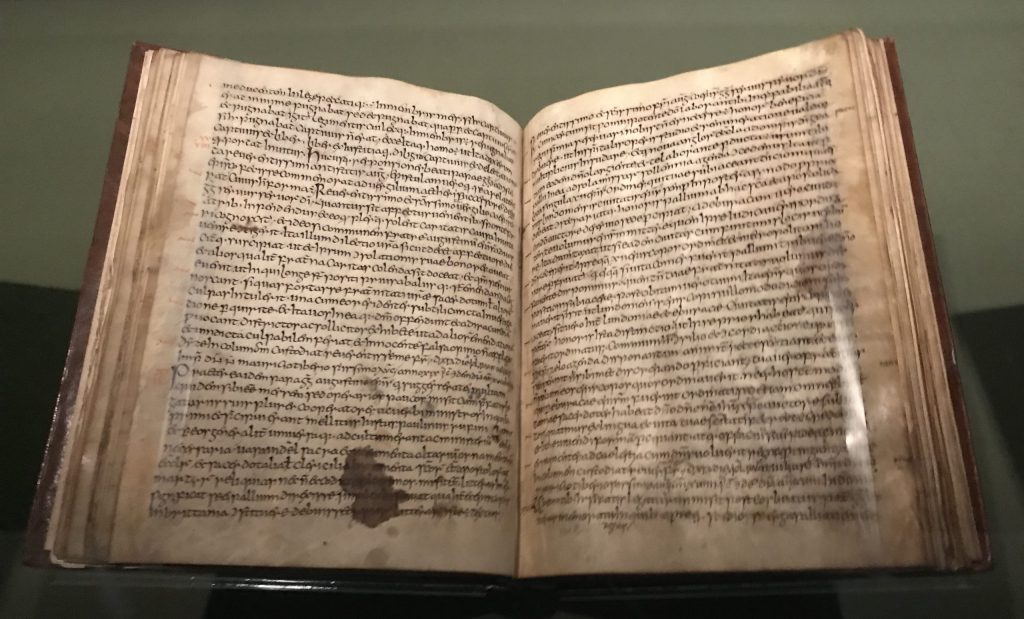

Another writer was Hugeburc, an English nun at the Benedictine monastery of Heidenheim in southern Germany. Hugeburc’s eighth-century account of the lives of two brothers, Willibald and Wynnebald, established her as the first named English woman writer of a full-length narrative. But, Hugeburc went one step further, and encoded her name within the manuscript. Unencrypted, and translated from Latin into English, the text reads: ‘I, a Saxon nun named Hugeburc, wrote this.’ Not only did this message help to preserve Hugeburc’s name for posterity, Watt explains, it also acknowledges her role as a writer.

Engaging with literary culture

While educational opportunities were limited for medieval women, religious houses provided nuns like Leoba and Hugeburc with access to learning. The double-monasteries at Whitby, Ely and Barking were important centres of women’s literacy, and were run by three founding abbesses: Hild of Whitby (614 – 680), Etheldreda of Ely (c.636 – 679) and Ethelburga of Barking (active 664). Within these intellectual powerhouses, nuns and monks worshipped and lived together, and had access to education and library facilities. The nuns were part of an active literary culture, and worked as scribes, authors and archivists. ‘We tend to nowadays ascribe the production of texts to single individuals, but many more texts were produced by the community,’ Watt says. ‘Texts were produced and exchanged amongst networks of readers.’

Women were also patrons of texts, and would request works to be written for their community. One such work was Aldhelm’s seventh-century prose treatise, De Virginitate, commissioned by Abbess Hildelith for her nuns at Barking Abbey. An esteemed scholar, Aldhelm was abbot of Malmesbury and Bishop of Sherborne. His text, De Virginitate emphasises the importance of virginity to women leading a celibate lifestyle. The text is written in a complex Latin, which, Watt explains, highlights the nuns’ academic prowess: ‘Aldhelm clearly assumes that the nuns have the linguistic abilities to read a very difficult text.’

His work also celebrates the literary culture of the abbey. He praises the nuns for the ‘rich verbal eloquence’ of their writing, and describes his joy at receiving letters from Barking. He even refers to the women as spiritual athletes, noting: ‘[they] are known to exercise the most subtle industry of their minds and the quality of (their) lively intelligence through assiduous perseverance in reading’ (De Virginitate, 61). By referring to the women as spiritual athletes – the term ‘athlete’ was typically applied to men in this period – Watt explains that Aldhelm regards the nuns as his spiritual equals. ‘They are capable of achieving the same level of spirituality as him,’ she says.

A forgotten legacy

But, following the eighth century, women’s engagement with literary culture declined. Women’s religious houses were disproportionately affected by the Viking invasions of the ninth century, which resulted in the loss of their libraries. ‘Many of the women’s religious houses were located at key strategic geographical points,’ Watt says, ‘sites such as Whitby Abbey – which was very exposed on the east coast of Northumbria – were right in the firing line when the Vikings arrived.’ The ninth century also saw the introduction of the Benedictine Reform, which restricted women’s access to scholarly communities.

Watt explains that there are several reasons why few women-authored texts from the early medieval period have survived. Many anonymous works have been automatically attributed to men, when they could in fact have been written by women. She cites the example of the Life of Gregory the Great, an eighth-century text produced at Whitby. While the text has been attributed to an anonymous monk at Whitby, Watt argues that its emphasis on the interests of women, could suggest it was produced by the abbey’s community of nuns.

Another reason, Watt argues, is that male monastic writers ‘overwrote’ existing texts written by women. ‘Male monastic writers would take sources and texts by women and integrate them into their own text,’ Watt explains. ‘In a sense, they would overwrite and replace these earlier works by women, which would then get lost because they were regarded as being out of date, or not as important.’ One such example, she suggests, occurs in Book Four of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which focuses on the early history of women’s religious houses. In this section, Bede alludes to the fact that many of the sources he has drawn upon were written by communities of women. ‘Bede has used these sources and sewn them together to make a larger narrative,’ Watt says. ‘We know for example, that he seems to have based his account of Whitby on an earlier life of Hild of Whitby, which hasn’t survived, and was probably written by her fellow nuns.’

At a time when issues surrounding gender diversity and inclusion still dominate headlines, Watt’s book highlights the integral role early women’s writing had on English literary history. From poets and patrons to archivists and authors, Watt amplifies the voices of these overlooked women writers, putting their achievements centre stage.

Diane Watt is Professor of Medieval English Literature at the University of Surrey. Her latest book Women, Writing and Religion in England and Beyond, 650 – 1100 is published by Bloomsbury bloomsbury.com/uk

This article first appeared in edition 134 of The Medieval Magazine. Find out more about the magazine: themedievalmagazine.com