On 15 June 1215, a document was sealed in the meadow of Runnymede, which would become a powerful symbol of democracy and individual liberties. Known as Magna Carta – meaning ‘The Great Charter’ – the legal document established the principle that everybody, including the king, was accountable to the law. The granting of the charter by King John marked a significant turning point in English history – the lead up to which had been characterised by crisis, warfare and rebellion. From religious disputes to heavy taxation, discover the origins of Magna Carta – and the places linked to this historic document.

How did Magna Carta come about?

Troubles with France

During the reign of King John (r.1199–1216), England experienced political and social unrest. When John succeeded to the throne, following the death of his brother Richard I (‘the Lionheart’), he became the subject of controversy. Richard had died without an heir, which triggered a succession dispute between John and his 15-year-old nephew, Arthur of Brittany. John was the successful claimant, and Arthur rebelled against him. In response, John imprisoned his nephew at Rouen, where he died in 1203 under mysterious circumstances.

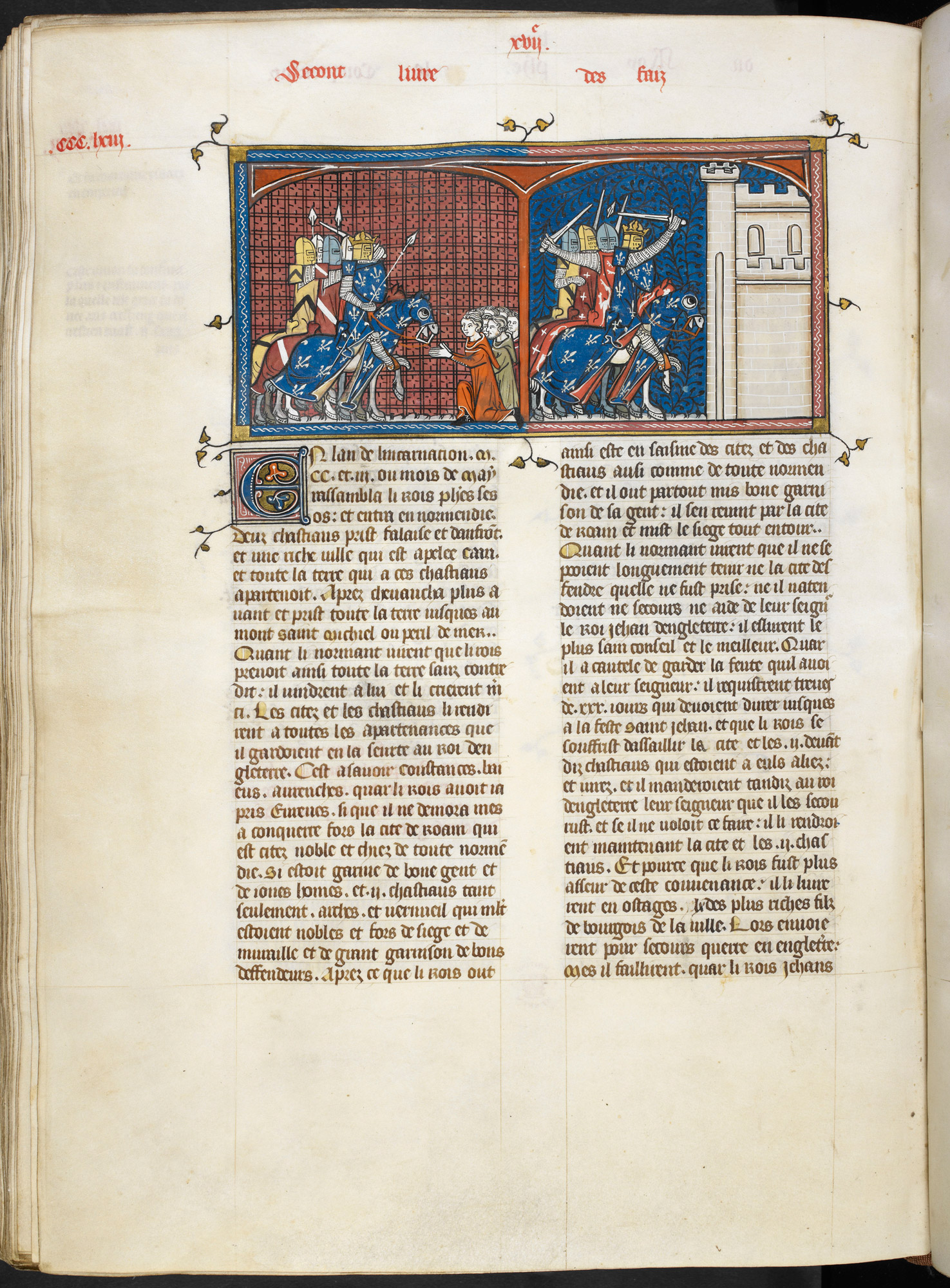

When John came to power, he inherited the Angevin Empire, which had been forged by his father, Henry II. Stretching from Scotland to the Pyrenees, the empire included vast areas of southern France, as well as Brittany and Normandy. But, following the death of Arthur of Brittany, the barons of western France launched an uprising. Demanding justice – and tired of their lands being used in warfare – they revolted against John, in a movement led by the French King, Philip Augustus. John was called to trial at the French court, but he refused to attend. In response, Philip declared that John had forfeited his lands in France. He seized back many of the French provinces, most notably Normandy in June 1204.

Difficulties with the Church

John’s problems didn’t stop there. Throughout his reign, John’s relationship with the Church became increasingly strained. In 1206, Pope Innocent III decided to appoint Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. Langton believed that kings should obey written law, and should only tax subjects in times of dire need – principles which John didn’t agree with. The King refused to let Langton take office, and the Pope responded by laying down an Interdict. Issued in 1208, Pope Innocent’s decree prohibited people in England from receiving the sacrament or being buried in consecrated ground.

The following year, Pope Innocent went a step further and excommunicated John from the Church. John responded by increasing taxes against the Church and English barons. Langton – along with other barons accused of treason – fled to France. After years of religious turmoil, John made peace with Pope Innocent in 1213. But, he had a tactical reason for doing so.

Since the loss of Normandy, John had been determined to reclaim his lost lands. As part of his plan to achieve this, John placed his realm under papal overlordship. This meant that the Pope would be obliged to protect England against the threat of a French invasion.

Stephen Langton was also allowed to return to England and was installed as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1213.

Discontented barons

In 1214, John launched a military campaign against France, funded by the extortionate taxes he had exacted from his barons. John and his forces suffered a crushing defeat, most notably at the Battle of Bouvines in northern France. But, in John’s absence, his barons had begun to conspire against him. Many refused to pay the taxes known as ‘scutage,’ which was intended to fund future campaigns in France.

Some also demanded reform. The rebel barons met with Archbishop Stephen Langton and a representative of the Pope to express their grievances against their king. Together, they called for John to adhere to the Coronation Charter which had been issued by King Henry I in 1100. The first surviving English Coronation Charter, Henry’s document contained a series of promises, which declared his intention to maintain good order, abolish tyranny and injustice, and rule according to custom and law. The barons urged John to issue a charter guaranteeing good government, which would be modelled on Henry I’s document.

Many drafts of the proposed document circulated between the barons and John – one of which is known today as the ‘Unknown’ Charter. Discovered in the French national archives in the 19th century, this document contains a copy of Henry I’s Coronation Charter, and a series of new clauses, which John is said to have agreed to.

However, tensions continued to rise. In May 1215, the barons declared war and renounced their allegiance to the king. Led by Robert fitz Walter, the barons captured the city of London. With the centre of royal government now in the hands of the rebels, John had no choice but to negotiate with them.

The sealing of Magna Carta

In the open landscape of Runnymede in southeast England, John met with the rebel barons in June 1215. Situated beside the River Thames, and between Staines and Windsor – the home of the royal residence, Windsor Castle – Runnymede was seen as neutral ground. Its location made surprise attacks difficult, and its marshland would be unsuitable for lengthy fighting.

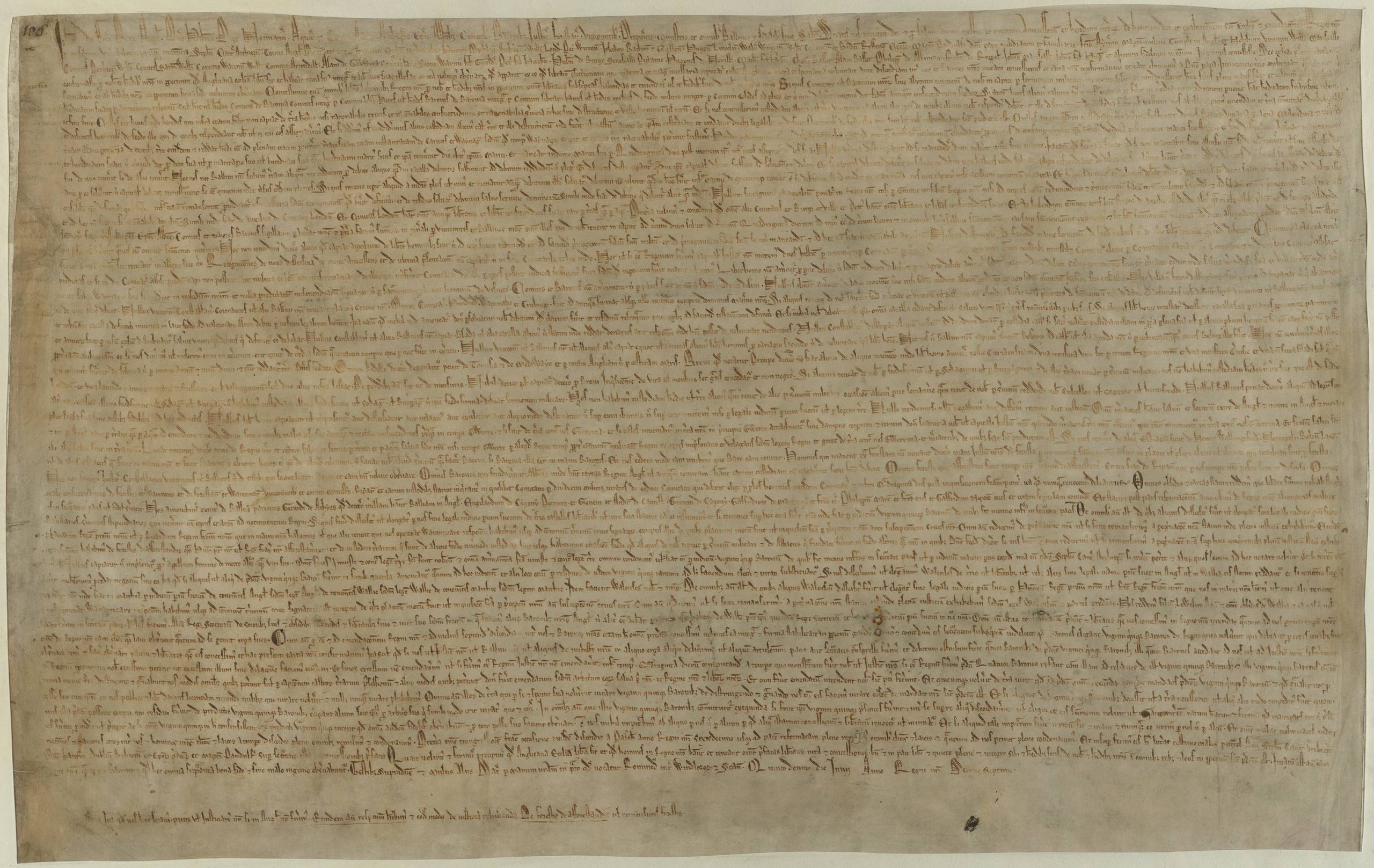

Following lengthy negotiations, a document was produced, known as the Articles of the Barons. Written in Latin, the document listed the terms of reform agreed with the king. This formed the basis of Magna Carta, which was sealed by King John on 15 June.

The contents of Magna Carta

One of the most significant documents in history, Magna Carta established for the first time the principle that nobody, not even the monarch, is above the law. The charter signed by King John contains 63 clauses. More than a third of the clauses relate to the power of the monarch, and clearly define the extent of the king’s authority. Others deal with taxation, the ownership of land, feudal rights and customs, and practical arrangements to restore peace.

Magna Carta also contains details about the administration of justice. Its most famous clauses include 39 and 40, which emphasise the right to justice and a fair trial by duty:

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.” Clause 39

“To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right to justice.” Clause 40

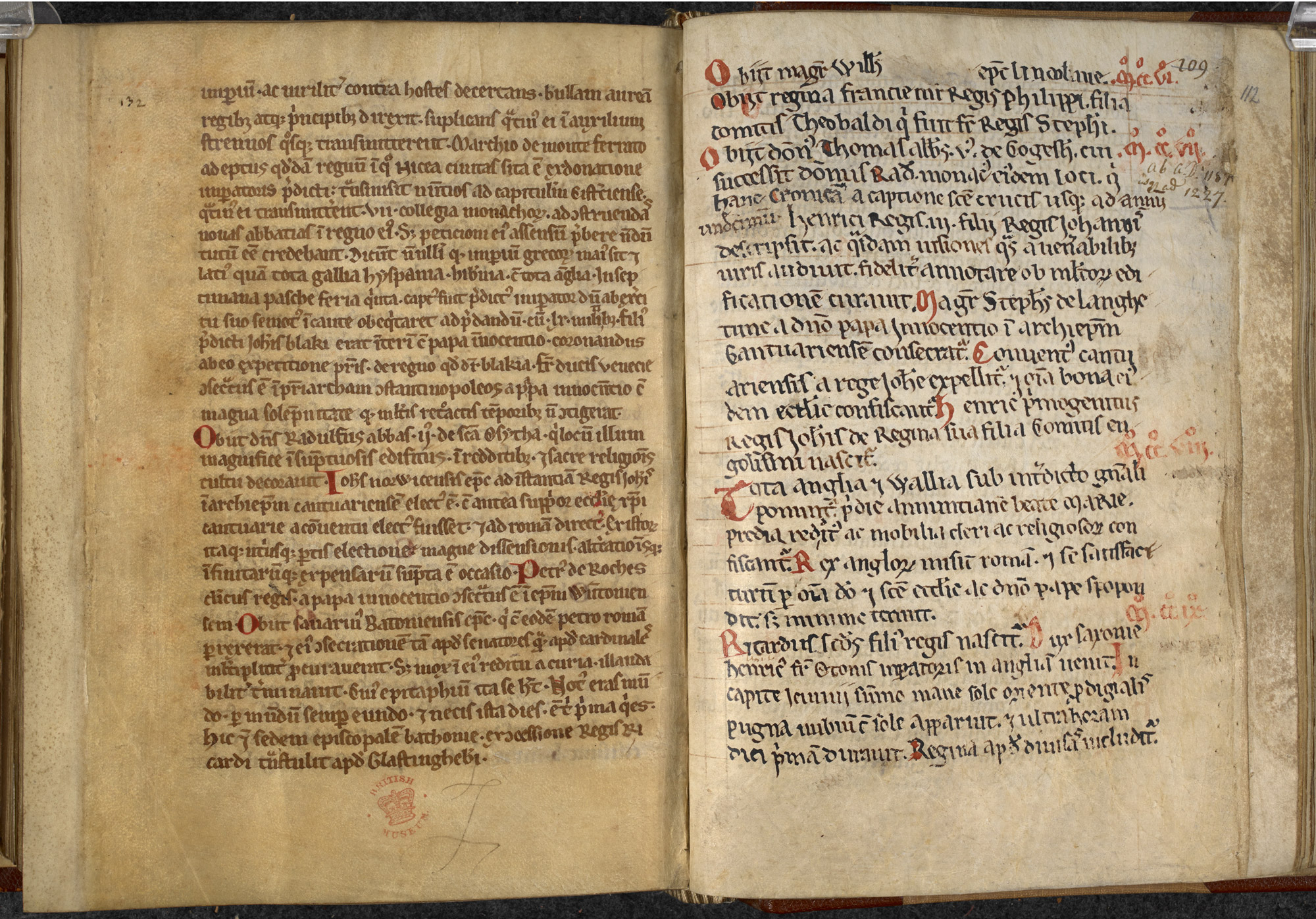

Scholars are unsure about how many copies of the 1215 Magna Carta were issued, but four copies still survive: two at the British Library, one in Lincoln Cathedral and one in Salisbury Cathedral. The charter was written on parchment, which was made from sheepskin. The scribes who produced Magna Carta wrote in Latin, using iron gall ink.

Popular in Europe right up until the 20th century, iron gall ink was made from ingredients including iron sulphate, water and tannins from oak galls (a growth on an oak tree).

On 19 June, the barons made their peace with King John and renewed their allegiance to him. However, this wasn’t to last. In the summer of 1215, John sent messengers to the Pope to request that Magna Carta be annulled, declaring that he had been forced to sign it. Shocked by the charter’s terms, Pope declared Magna Carta ‘null and void of all validity for ever.’ Up in arms at this turn of events, the rebel barons first seized London, and in September 1215, civil war erupted. The barons called on the French army to support their cause, and Prince Louis of France was invited to be the new king of England. When King John died of dysentery in 1216, England was still at war.

While the power of Magna Carta appeared to have diminished, the great charter was resurrected during the reign of King Henry III. In 1216, a revised version of the charter was established in his name, and following the expulsion of the French army in 1217, another version was also issued. The definitive version of Magna Carta was issued by Henry III on 11 February 1225.

Today, only four clauses from Magna Carta are still valid in UK law, which cover matters, including the freedom and rights of the English Church, the right to justice and a fair trial, and the liberties and customs of London and other towns.

Runnymede – the site of Magna Carta

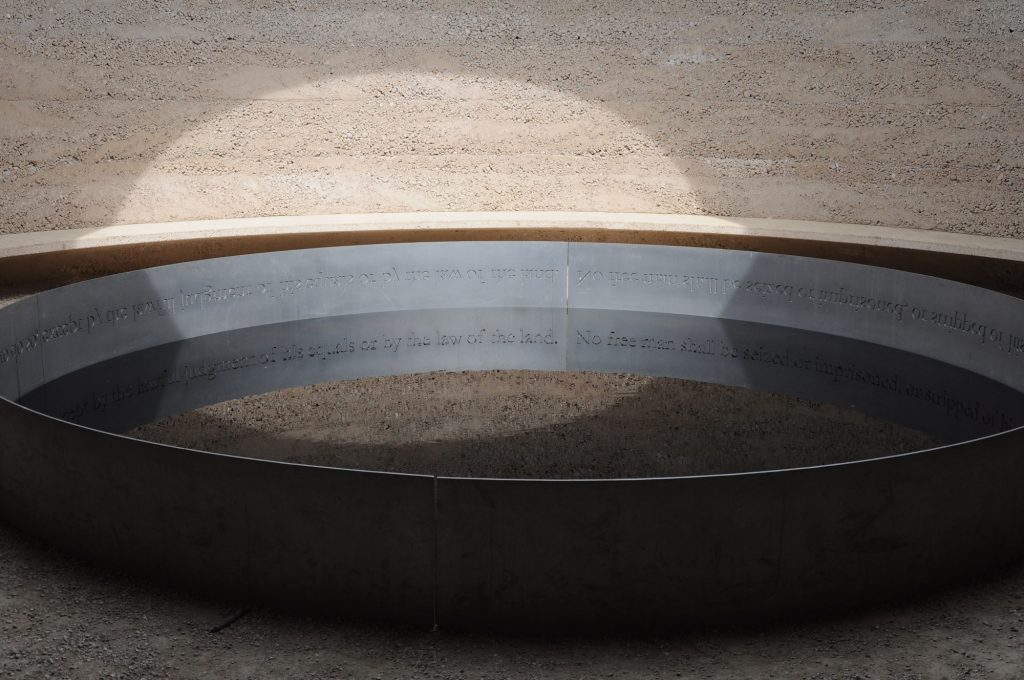

A vista of riverside scenery, meadows and hills, the ancient landscape of Runnymede provides a tranquil setting for reflection and enjoyment today. Looked after by the National Trust, the site has several contemporary installations which respond to its unique history.

Framed by fields and woodland is a circular building known as Writ in Water. Created by artist Mark Wallinger, the artwork is inspired by labyrinths: a choice of passageways lead visitors into a central chamber. A hushed atmosphere envelops this inner sanctum, which contains a round pool, mirrored by a circular opening above. Inscribed into the curves of the pool are words from Clause 39, which are reflected in the water.

Just a short distance from Writ in Water, twelve bronze chairs can be seen standing in an ancient meadow. Created by artist Hew Locke to mark the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta in 2015, The Jurors invites viewers to examine the ongoing significance of Magna Carta. Each chair incorporates symbols connected to key moments in the struggle for freedom and equal rights. A portrait of poet Phillis Wheatley – the first published African American woman – is carved on one chair. On another, a reference from Oscar Wilde’s work The Ballad of Reading Gaol can be seen, which describes the dehumanising effect of the prison system.

More than 800 years after it was sealed, Magna Carta remains a powerful symbol of democracy, human rights and freedom from tyranny.

One thought on “What is Magna Carta?”