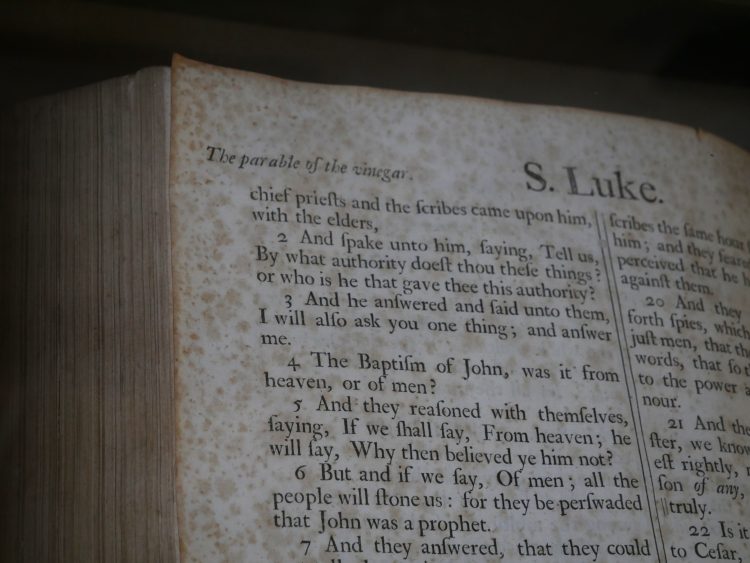

Nestled close to the altar of St Mary’s Church in Chiddingstone in Kent is a Bible with an extraordinary story. Known as the ‘Vinegar Bible,’ this rare edition of the King James Bible takes its name from a misspelling of ‘the parable of the vineyard’ in Luke 20:9 as ‘the parable of the vinegar.’ While the ‘Vinegar Bible’ was praised for its elaborate decoration, the numerous textual mistakes irrevocably damaged the reputation of the Bible’s printer, John Baskett.

Yet, despite its controversy, the ‘Vinegar Bible’ offers an insight into the complex and carefully controlled production of English Bibles, which occurred in the centuries prior to its publication. Here, explore the series of events that led to the creation of this distinctive Bible.

The story of English Bible printing

At the time of the Vinegar Bible’s publication in 1717, printing the Bible in English was tightly regulated.

The history of Bible printing in England has its origins in the mid 15th century, when Johannes Gutenberg developed the printing press in the German city of Mainz. His invention was revolutionary, enabling the mass production of books and the rapid spread of knowledge across Europe. The Gutenberg Bible, published in around 1455, was the earliest full-scale work printed in Europe using moveable type.

The printing industry took Europe by storm, with printing presses being set up in cities such as London and Edinburgh. The mainstay of the industry was religious texts, including Bibles, books of hours and psalters. Crucially, the printing press made it possible to print the Bible in vernacular languages, such as English, rather than Latin, the language of the Catholic Church.

A turbulent history

However, printing the Bible in English wasn’t without its dangers. Since the 15th century, the translation of the Bible into English had been banned in England. In 1401, Henry IV introduced a new law titled ‘De Heretico Comburendo’ or ‘On the Burning of Heretics’, which outlawed the translation of the Bible. It also made heresy a crime, punishable by burning at the stake.

This legislation had been enacted in response to the writings of John Wycliffe, a 14th century scholar. A religious reformer, Wycliffe believed that the Bible – which was written in Latin – should be accessible to everybody.

In the late 14th century, scholars connected with Wycliffe produced an English translation of the Bible – the first complete copy of the sacred text in the English language. While not burned as a heretic during his lifetime, Wycliffe’s views, which included his concerns about the corruption of the Church, were shared and taken up by his followers, known as ‘Lollards.’

In an effort to further suppress Lollard activities, the Constitution of Oxford was passed in 1408, which prohibited the translation of the Bible into English, unless licensed by a bishop. The legislation also forbade the possession of translated Bibles.

The rumblings of religious revolution came to a head in the 16th century, a period marked by conflict and reform. In 1517, the German theologian, Martin Luther, published his ninety-five theses, which challenged the authority of the Catholic Church. Luther’s words were soon published across Europe, sparking debate and dissent. In 1534, he published his German translation of the Bible, enabling the wider public to read and understand the Bible in German – a move that further undermined the authority of the Church. His actions set in motion a revolution that would shatter the power of the Catholic Church and lead to the creation of Protestantism: a movement known as the Protestant Reformation.

Around the same time as Luther was publishing his writings, a theologian known as William Tyndale was working on his own English translation of the New Testament. In order to circumvent the ban on translating the Bible in English, Tyndale had his translation printed in Cologne, Germany. But, shortly after printing began in 1525, his project was discovered. With production halted, Tyndale fled to Worms in western Germany, where he had a new edition printed in 1526. While owning a copy of Tyndale’s New Testament was an offence punishable by death in England, copies were smuggled into the country and sold. Many of these were destroyed by the authorities: today, only three copies of this edition are thought to have survived.

With his life in danger, Tyndale went into hiding. In 1535, he was arrested in Antwerp in Belgium and held prisoner in Vilvoorde castle, located just outside Brussels. After being convicted as a heretic, Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake in October 1536.

Henry VIII and the English Bible

Over in England, religious turmoil was escalating rapidly. In 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which established Henry VIII as the head of the Church of England and severed ecclesiastical ties with Rome. This was because the Pope had refused Henry’s attempts to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne Boleyn.

As the Supreme Head of the Church of England, Henry needed a new English Bible. But, there was a problem. The best printed English translation of the Bible was Tyndale’s controversial edition of the New Testament. Keen to disassociate themselves from the convicted heretic, Henry and his bishops granted Royal licenses for two other Bibles to be produced.

The first of these was the Coverdale Bible: the first complete Bible in English. Translated by Miles Coverdale, the work was originally published abroad in 1535. A new edition of this Bible was produced in 1537, with the authorisation of Henry VIII. Complete with illustrations, Coverdale’s large size bible coined phrases such as ‘winebibber’ – a habitual drinker of alcohol.

In the same year, Matthew’s Bible was published. Attributed to Thomas Matthew, this Bible is thought to have been written by John Rogers, a disciple of Tyndale’s. However, unbeknownst to Henry, this Bible was virtually unchanged from Tyndale’s version.

With neither the Coverdale nor Matthew’s Bible satisfactory, a new Bible translation was commissioned by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s vicegerent in spiritual matters. Published in 1539, the ‘Great Bible’ was designed to be the country’s authoritative sacred text, set up in every cathedral and parish church.

The emergence of Bible patents

While circulation of the Bible in English had become legal in 1536 following Henry’s break with Rome, production of the sacred text was still carefully controlled.

During Henry VII’s reign, the position of Royal Printer was established, which brought with it the right to print Acts of Parliament, statutes, proclamations and injunctions.

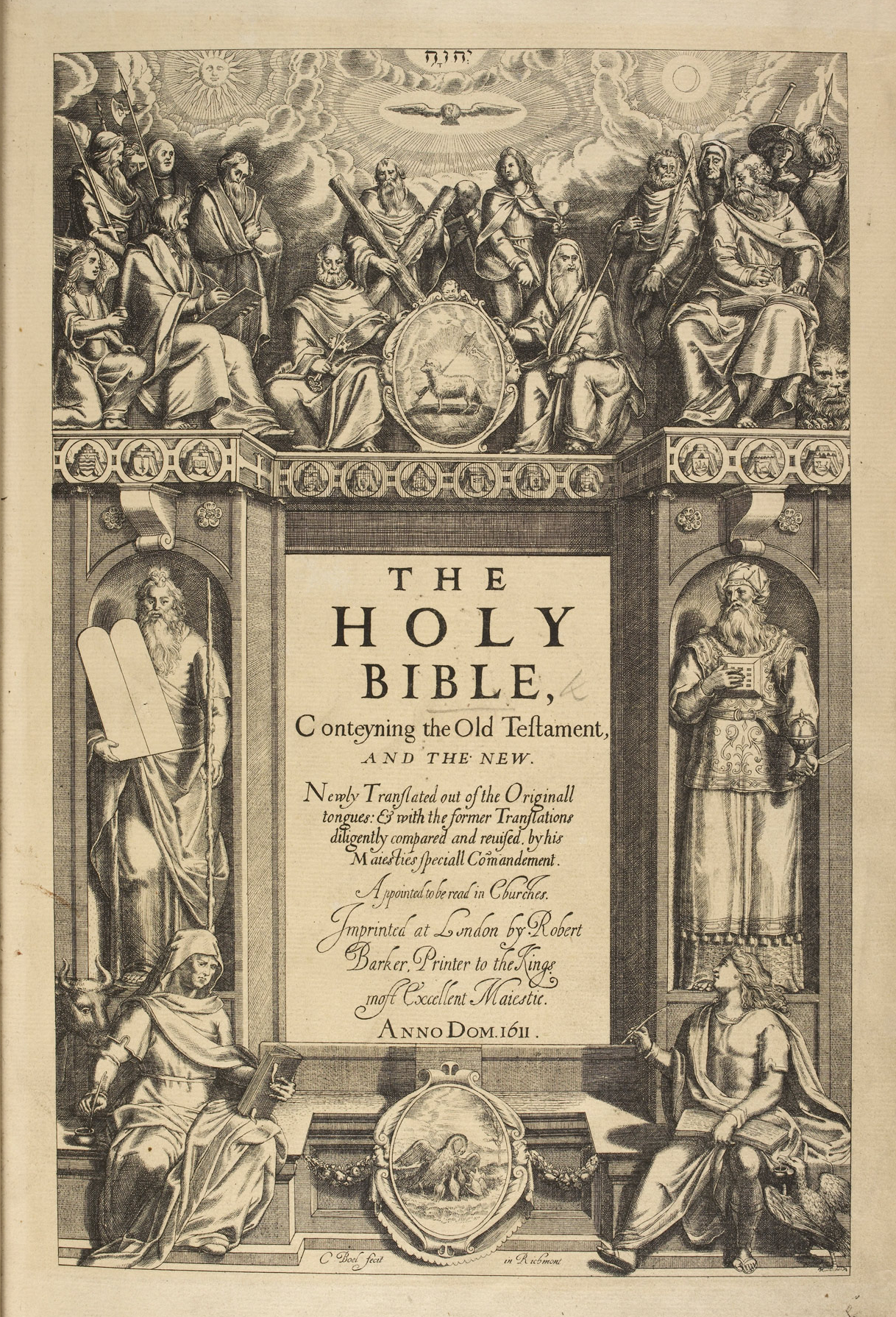

In 1577, Elizabeth I established a Royal Printers’ Patent, which gave the holder the privilege to print all Bibles and Testaments. The first recipient of this patent was the publisher, Christopher Barker. The patent was taken up by his son, Robert Barker, who became part of an ambitious project that would transform the course of the English language.

The publication of the King James Bible

In 1604, James I appointed a team of scholars to create a new English Bible, which would draw on the best available translations and sources. After seven years of work, the King James Bible was completed and printed by Robert Barker in 1611. The new Bible was appointed to be read in churches and contained several interesting typographical features, such as the ‘long s,’ pronounced as a modern ‘f’.

Not only a pioneering religious text, the King James Bible had a profound influence on the English language, which is still evident today. Many of its phrases permeate everyday language, including sayings such as ‘at their wits end’, ‘a law unto themselves’, ‘fallen from grace’ and ‘fell by the wayside.’

A lasting legacy

More than 400 years after it was published, the King James Bible remains the most widely published text in the English language. Across the English-speaking world, it continues to leave a lasting influence on religious life, culture, politics and literature.

The ‘Vinegar Bible’ on display in St Mary’s Church in Chiddingstone is part of this wider story of religious conflict and debate that shaped the history of the English Bible.

thanks very interesting