The fifteenth century saw the emergence of continental women’s mystical works appearing in England, facilitated by the early printed textual tradition of Wynkyn de Worde and William Caxton (Grisé Holy Women in Print 83). Indeed, the translation of the works of women such as St Catherine of Siena (1347-8), St Bridget of Sweden (c.1302/3-73), and St Elizabeth of Hungary (1294-1336) into the vernacular of English, taps into the wider cultural context surrounding female reading and writing practices. Scholarship has often focused on how Paul’s statement in I Corinthians that women should: “keep silent in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak ” was instrumental in barring women from education (I.Cor.14.34). Under the restrictions of the repressive patriarchal system, women were forbidden from preaching and teaching the word of God, believing it provided them with “a form of authority over men” (Green 24). Furthermore, women’s exclusion from education prevented them from being able to read Latin, the language of clerical literature. In order to combat this, women played an influential role in the development of “vernacular translations” (Groag Bell 150), a move which was not without controversy as it represented a significant threat to “the supervisory control of the clergy” (Green 37).

Alexandra Barratt in her essay “Continental women mystics and English readers” emphasises the influence of continental women upon English medieval women, stating that “their very existence […] nourished extraordinary and until then unthinkable ambitions in their readers” (254). Barratt’s emphasis on “nourishment” creates associations of connectivity and maternal guidance, and indeed, Grisé attributes the success of the works of continental women in England to their being “examples for the readers in how to live virtuous lives and […] instructing the audience on good Christian living” (83 HWIP). Grisé’s statement can be developed to highlight how through the spiritual guidance these continental works offered, continental women effectively became spiritual mothers to English women.

The sense of connectivity and community that these continental works fostered between English women forms a significant part of this dissertation. In his book The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, Brian Stock coins the term “textual community” in order to describe communities which were founded upon “interactions between members of groups which were […] structured by texts” (91). The sense of inclusion that was at the core of these textual communities is emphasised by Felicity Riddy who notes the increased engagement and similarities between the literary culture of nuns and laywomen “[which] not only overlapped but were more or less indistinguishable” (110). Through book ownership and book bequests of continental texts from laywomen to religious communities, this emphasises the fluidity and scope of textual communities, not simply confined to the world of the family and the convent. Even illiterate women could also participate in looser textual communities, with depictions of continental saints in church iconography encouraging the congregation to map their own stories onto these images.

This notion of the variety of ways of reading in the medieval period lends itself to an analysis of the meaning behind this dissertation title. “Cultivating Communities” emphasises the sense of intimacy between continental women and the female reader, working to help her lead a virtuous Christian life, and how this can be used to the benefit of the community, whether that be the unit of the family or the convent. The title’s focus on the “Literate Practices” of medieval women emphasises that the idea of literacy in the medieval period is more nuanced, not simply depending on whether one could read a book, but encompassing oral ways of reading. This idea is reinforced by Stock who states “one of the clearest signs that a group had passed the threshold of literacy was the lack of necessity for the organising text to be spelt out, interpreted, or reiterated” (91).

Indeed, this dissertation will unpack the elements presented in these continental texts that resonated so strongly with English medieval women. For religious women, in particular those in the Bridgettine House of Syon Abbey (an order founded by St Bridget), the dissertation will analyse how St Catherine of Siena’s Orcherd of Syon promotes the importance of community building. The didactic use of domestic imagery in St Bridget of Sweden’s Revelations will be considered to emphasise how this highlights the re-appropriation of continental religious women from the convent into the domestic lay household , working to reinforce familial relationships. St Elizabeth of Hungary’s Revelations will be discussed in conjunction with The Book of Margery Kempe to illustrate how Margery models her life on those of continental female visionaries. Indeed, this section will discuss how these visionary writings made such an impression on Margery, that despite her status as an illiterate laywoman, she enlisted the help of a scribe in order to add her voice to this female mystical tradition. As examples of the genre of women’s mystical experiences, these three continental texts therefore instruct and highlight the values needed to achieve spiritual fulfilment in similar ways.

It can be argued that the works of these continental female writers facilitated the development and breadth of textual communities in the period, and by being viewed as spiritual mothers in the medieval popular imagination, moving between the world of the religious and the domestic household, these continental women served to represent and promote inclusion. Indeed, the structure of this dissertation emphasises the widening circulation of these continental female writers throughout England. The chapters work to chart this movement from exclusive to inclusive communities, progressing from the enclosed cloisters of the convent, then emphasising the increased interaction between female lay and religious communities, before branching out to the larger community through different ways of reading, thereby extending the influence of continental women to a larger audience.

Continental Women and the Community of the Convent

It has been estimated that in the Middle Ages there were around 144 nunneries (Bell 33), with convents acting as a “foci for female interaction” (Erler 12). Scholarship has often focused on how despite “the trend of medieval thought […] [being] against learned women”, convents were key sites for female literacy (Power 238). The Bridgettine house of Syon Abbey, a double order founded in 1415 by St Bridget of Sweden, played an influential role in encouraging the literacy of medieval religious women, emphasising the importance of “personalised, introspective piety” (Jones and Walsham 13). Most significantly, the network of books commissioned for Syon Abbey by continental women, such as St Catherine of Siena, highlights the Abbey’s influence on an international level. Indeed, this point can be developed further to argue that continental women played an influential role in establishing convents, in particular Syon Abbey, as key sites for female literacy with their commissioned works helping to guide and cultivate the spirituality of English medieval nuns.

The importance of reading for the nuns at Syon is highlighted by Bridget’s Rewyll of Seynt Sauiore (a series of rules for the community at Syon to abide by), in which she states that “Bookes also are to be had as many as be necessary to doo dyvyne office […] Thoo bookes they shalle haue as many as they wylle in whiche ys to lerne or to studye” (Hogg 77). Scholars including D.H. Green and Virginia R. Bainbridge, have frequently discussed how the wealth of vernacular literature produced for the nuns at Syon highlights the proactive role the nuns played in furthering the development of the vernacular, resulting in Syon being internationally regarded as “an intellectual powerhouse of ecclesiastical reform” (Bainbridge 82). Indeed, as mentioned above, the network of books commissioned for the Abbey by continental women emphasises how the nuns “stood at the fore-front of English spirituality”, with one of the most notable Syon commissioned works being St Catherine of Siena’s The Orcherd of Syon (Green 252). The Orcherd of Syon was initially written in Italian (Dialogo) in 1378 and was translated into Middle English in manuscript form (Barratt CWM 251). Most notably, the Orcherd was published in 1519 by Wynkyn de Worde, with the Middle English translation aiming to “provide nuns with small portions of doctrinal food for contemplation and meditation” (Despres 155).

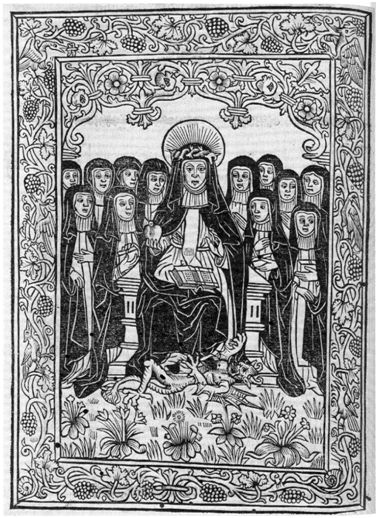

The woodcut of St Catherine of Siena surrounded by twelve nuns, from Wynkyn de Worde’s printed edition of The Orcherd of Syon (1519), reinforces the view of convents as key sites for female literacy (Fig.1). Indeed, the woodcut’s focus on Catherine reading, with a community of nuns devoutly listening, not only works to naturalise women as readers, but emphasises female religious communities as the intended readership of the Orcherd, highlighting this textual community in action. This intended readership is reinforced by the Translator’s Prologue to Wynkyn de Worde’s printed edition of The Orcherd of Syon, where the translator comments that the book was commissioned for the “religyous modir & deuoute sustren” of Syon Abbey who dwell “in the blessid vyneyard of oure holy Saueour” (Hodgson and Liegey 1). Indeed, this imagery stems from Bridget’s Rewyll of Seynt Sauiore where Christ uses the metaphor of a vine to command Bridget to create the Bridgettine Order: “I shal plante me a vyneȝerde of newe, in which þoue shalt bere the brawnches of my wordes” (61), an Order which is designed: “principally by women to the worshippe of my most dere beloued modir” (61). In the woodcut, the reference to the “vyneyard” is further highlighted by the images of blossoming flowers and berries, giving the sense of an organic community, one which is flourishing under the protection of the Saviour. This is continued later on in the Translator’s Prologue: “Þis book of reuelaciouns as for ȝoure goostly comfort to ȝou I clepe it a fruytful orcherd” (1). In the Prologue, it can be argued that the image of the “frutyful orcherd”, highlights the translator’s thoughts on how the nuns should read and benefit from this work.

Grisé draws upon this idea, arguing that the allegory of the orchard throughout the text, makes the text itself become “an orchard, with the writer as gardener and the reader as the Syon nun traversing the grounds” (Female Religious Readers 204). Grisé’s statement with the reference to the Syon nun “traversing the grounds” focuses on the fluid nature of the Orcherd, emphasising the multiple ways the nun can walk and therefore choose how to negotiate the text. However, Grisé’s distinction between the writer as a “gardener” and the nun as a passive wanderer through the grounds, I would argue is too rigid, thereby preventing the nun from actively harvesting the text for her spiritual instruction. Indeed, I will draw upon Grisé’s reading to argue instead that the use of such organic imagery throughout the text, serves a more communal function, acting as a metaphor for the flourishing intellectual female community at Syon.

For the nuns at Syon, organic imagery in the Orcherd serves a didactic function. This is illustrated in the section Prima Pars, when Christ instructs Catherine to “þinke þat a soule is a maner tre which comeþ out of loue; […] [which] may nat be norisched but of a loue of þe soule ooned to þe loue of God” (39). The representation of the soul as a tree, emphasises how the nuns’ spiritual fulfilment can be cultivated through having a close relationship with God. Indeed, this metaphor is extended further by Christ to emphasise to Catherine, as well as the nuns at Syon, the values needed to achieve such spiritual fulfilment “þe tre of charyte is norischid in mekenes, bryngynge out of hym bisyde þe tre […] parfiȝt discrecyuon” (39).

Most significantly, the nature of the revelations in the Orcherd are frequently concerned with community building, with Christ instructing Catherine about how to achieve fruitful relationships with neighbours. Again, this is emphasised through the metaphor of the tree:

“Þis tre, whanne it is myrily plauntid, it buriowneþ out smyllynge or swete floures of vertues, […] and bryngeþ forþ fruyt of dyuerse gracis to þe soule, that same soule ȝeldynge also to his neiȝbore þe fruyt of profyȝt” (39-40).

In this passage, individual virtues are associated with images of vitality and reproduction, “smyllynge or swete floures of vertues” and ” bryngeþ forþ fruyt of dyuerse gracis to þe soule”. These individual virtues are described as subsequently instilling virtuous behaviour in others “that same soule ȝeldynge also to his neiȝbore þe fruyt of profyȝt”. The importance of cultivating a fruitful community, is reinforced through the allegory of the vineyard, where humanity is presented as the Lord’s workers, labouring “in þe vyneȝerd of holy chirche” (63), as part of the “body of cristen religyoun” (63). Indeed, the depiction of the Church as a “vyneȝerd” promotes inclusion, with the vineyard’s branches working to connect humanity as a family, labouring together for the purpose of Christianity. Not only does this labour benefit the individual, the vineyard allegory is extended to show how this connectivity benefits the community: “w[hi]l[e] þei laboure aboute her owne vyneȝerd, þei tilyen þe vyneȝerd of her neiȝbore, for þat oon may not be tilied wiþouten þat oþit” (66). The gendered emphasis on tilling the “vyneȝerd of her neiȝbore” would resonate especially with the nuns at Syon, stressing the importance of female interdependency.

Throughout the Orcherd, organic imagery provides a “more accessible” way to teach the readers (in this case the nuns at Syon Abbey), about the values needed to foster a successful community (Grisé Syon and English Books 142). Catherine’s Orcherd, therefore, illustrates the active role continental women played in helping English medieval nuns with their spiritual guidance, teaching them how to achieve valuable relations with one another, to the benefit of their religious community. Indeed, the image of the “frutyful orcherd” can be extended beyond the text to act as a metaphor for the female textual community at Syon Abbey. Through the image of the flourishing orchard, it highlights the thriving intellectual female community at Syon as active consumers of, and inspiring, new Continental publications. Furthermore, the expanding orchard emphasises how Syon’s textual network is spreading outwards, extending the texts of these Continental female writers to a wider audience.

Lady Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII, played a significant role in extending Syon commissioned books, such as the Bridget attributed Fifteen Oes from the convent into the wider community. As a result of her status as a laywoman, combined with the restrictive system of female learning, which prevented women from learning Latin, Lady Margaret was denied access to the world of clerical reading. However, despite these setbacks, Lady Margaret was instrumental in “the distribution of English-language writings” (Krug 102), and in 1491 she commissioned William Caxton to print the Fifteen Oes in Middle English (Barratt Continental Women Mystics 250). Indeed, The Fifteen Oes is a series of prayers emphasising the physical passion of Christ, with each prayer calling upon Christ to “accepte my [the speaker’s] soule” (13), and show “mercy to me in the hour of my deth” (Fifteen Oes 7). Grisé states that the Fifteen Oes gained “immense popularity” (HWIP 90), amongst readers, and it can be argued that the Fifteen Oes’ emphasis on “physical and spiritual protection”, would have resonated with laywomen who were unable to access the world of the cloister (Krug 95). Again, the use of imagery which, for example, compares the blood of Christ to “a rype clustre of grapes” (Fifteen Oes 13), locates the religious concepts discussed in the text within the world of the familiar, making the work more accessible for laywomen readers. Lady Margaret’s active role in publishing the Fifteen Oes in Middle English, emphasises how it was possible for women to navigate around the repressive patriarchal system and publish texts that would enable laywomen to read and access devotional texts despite “their lack of Latin” (Green 146). As a result of Lady Margaret taking this Syon commissioned work and publishing it, this works to spread the influence of continental female writers out to the wider community.

Extending the Communities: From the Convent into the Home

Lady Margaret Beaufort’s active role in extending the texts of these continental medieval women beyond the community of the convent and into the households of laywomen, highlights the “permeability of female lay and religious culture” (Green 5). Indeed, the transition of these mystical continental women from their religious context to being absorbed into the domestic lay household is highlighted by the popularity of St Bridget of Sweden amongst laywomen. The authoritative Latin edition of St Bridget of Sweden’s Revelations (the Liber Celestis), which documents the visions Bridget experienced from Christ after her husband’s death, was transcribed in around 1377 by the Spanish bishop, Alphonse (Hutchinson Review 217) . Indeed, it was this edition that subsequently “facilitated [the] circulation of the Revelations and their translation into a number of vernaculars”, including Middle English (Hutchinson Review 217). Bridget’s popularity in England has been frequently discussed by scholars such as F. R. Johnston and Ann M. Hutchinson, with Hutchinson stating that Bridget “came to exercise a profound influence on English spirituality, both of the laity and the religious” (Hutchinson Reflections 69). Arguably, Bridget’s Revelations, with their didactic emphasis instructing women, both religious and lay, on how to lead a virtuous life, confirmed for the medieval popular imagination the view of Bridget as a spiritual mother. Bridget’s popularity in both the community of the convent and the medieval household highlights the increased interaction between female lay and religious communities. In the case of medieval laywomen, it can be argued that Bridget’s status as a spiritual mother played an influential role in reinforcing female familial relationships, extending to the creation of familial textual communities.

The influence of St Bridget of Sweden’s Revelations in strengthening female to female relationships through textual communities and book ownership is highlighted by Cicely, Duchess of York (1415-1495). As the wife of Richard, Duke of York and the mother of Edward IV and Richard III, Cicely’s status as a royal laywoman enabled her to own a vast collection of devotional works, including St Bridget’s Revelations (Armstrong 80). Indeed, the influence of St Bridget on Cicely’s piety has been the topic of scholarly discussion, with Denise L. Despres arguing that Cicely’s religious devotions were “in imitation of continental ecstatic women” (149). The extent of Cicely’s devotion to “continental ecstatic women” is highlighted by her dinner requests that she be read “writings of St Bridget […] [which] would form the conversation later during supper” (Despres 149). Through this daily reading routine of visionary texts, this highlights how continental women such as Bridget were becoming ingrained in the lives of Cicely and her gentlewomen, acting as spiritual mothers to actively shape their piety. By reading these texts at the dinner table, it created a safe and intimate space where female advice could be shared, and the spiritual messages gained from the text discussed, forming a familial textual community “in imitation of religious communal life” (Despres 149).

F.R. Johnston states that “Cicely’s devotion to St Bridget impressed itself on her family” (86), and indeed, in Cicely’s will, she bequeathed her copy of St Bridget’s Revelations to her granddaughter Anne de la Pole. This bequest highlights Bridget’s significant role in strengthening Cicely’s female textual community through book ownership. Susan Groag Bell corroborates this point, arguing that: “Medieval women’s book ownership reveals a linear transmission of Christian culture and development of […] [a] matrilineal literary tradition that may also have influenced later generations” (179). In the case of Cicely, her matrilineal transmission of Bridget’s book highlights how Cicely has drawn upon Bridget as a spiritual mother, and is now becoming a spiritual mother figure to Anne, extending the knowledge of her Christian piety which she learned from Bridget’s text, to subsequent female generations. Most significantly, Cicely’s admiration of Bridget was extremely influential for Anne who later became a prioress in the Bridgettine house of Syon Abbey (Johnston 86). As a spiritual mother figure to the nuns, Anne highlights the increased engagement between religious and lay communities who formed “part of the same textual community” (Riddy 111).

C.A.J Armstrong states that the popularity of St Bridget’s Revelations for English laywomen like Cicely was due to Bridget being “exotic and almost terrifyingly austere” (87). Armstrong’s focus on Bridget as “exotic” and “terrifyingly austere” has negative associations of otherness and detachment, whereas I would argue that the Revelations‘s focus on Bridget’s family struggles, was one of the reasons why her text was so influential amongst laywomen. Indeed, the tensions that arise when Bridget tries to balance her role as a mother to eight children with her spiritual worship, is highlighted in the Revelations by Christ’s command that she must “love me with all your heart, not as you love your son or daughter or relatives, but more than anything in the world” (Searby and Morris I.1.9). In Book VI of her Revelations, the difficulties that Bridget faces as a mother is highlighted by her anxious prayer to Christ, imploring Him to help her in “this trial” to support her daughter Katherina whose husband is dying (VI.118.8). Hopenwasser and Wegener argue that Bridget “shows insecurity with respect to parenthood” (64), and in this section, Christ alleviates Bridget’s worries, reassuring Bridget that He “will provide for her [Katherina]” (VI.118.8) and advising Bridget to let Katherina stay with her in Rome rather than travelling back to Sweden to see her dying husband. Through documenting her struggles and anxieties in motherhood, it is clear to see why Bridget’s Revelations resonated with laywomen like Cicely, portraying her not as an untouchable saint, but a relatable mother who “inhabited [the] world of real people and shared their experiences” (Hutchinson 71).

Indeed, the grounding of St Bridget’s Revelations in the familiar world of the domestic, works as an accessible means to instruct laywomen on how to achieve a virtuous Christian life. In Book One, Christ uses household furniture as a metaphor to explain to Bridget the values she needs to have in order to accept Him into her heart. These include a bed “where you can rest from the base thoughts and desires of the world” a seat “your intention of staying with me” and a lamp “the faith by which you believe that I am able to do all things” (I.30.9). By attaching spiritual meaning to these domestic images of the bed, seat and lamp, with their associations of comfort and warmth, Christina Whitehead argues that this reinforces the idea “that domestic, everyday space can be sacred space” (237). Whitehead’s argument can be extended further to argue that by making the domestic sacred, this promotes inclusivity, which for medieval laywomen would have been inspiring, as it highlights that Christ does appear to women outside the convent.

Throughout the Revelations, the Virgin Mary acts as a female role model and spiritual mother for Bridget. The first revelation Bridget receives from the Virgin draws again upon domestic imagery, with the Virgin using clothing as symbolism to explain to Bridget the qualities she must possess in order to lead a virtuous Christian life: “the underbodice is contrition. Just as the underbodice is worn closest to the body, so contrition and confession are the first way of conversion to God” (I.7.2), and “the cloak is faith. Just as the cloak covers everything and everything is enclosed in it, human nature can likewise comprehend and attain everything through faith” (I.7.4). The Virgin’s reference to the feminine “underbodice” stressing its closeness “to the body”, emphasises the intimate and bodily nature of female worship. However, the image of the underbodice can be extended to highlight the personal support the Virgin provides to Bridget.

The bodily nature of Bridget’s female worship is highlighted in her Christmas Eve revelation, where she is described as being in such a state of exaltation that “she felt a wonderful sensible movement in her heart like that of a living child turning around and around” (VI.88.1). Bridget’s affective piety is different from that of the loud bodily crying of other mystics such as St Elizabeth of Hungary and Margery Kempe (the specific details of their affective piety and its contextual history is discussed in the next chapter), as this bodily womb experience highlights her new found status as a spiritual mother. Indeed, upon hearing about Bridget’s experience, the Virgin reassures Bridget that it was not an illusion, stating “we want to indicate our intentions to friends and to the world through you” (VI.88.7). In their introduction to Books VI- VII of Bridget’s Revelations, Denis Searby and Bridget Morris discuss the significance of the Virgin’s statement, arguing that it provides Bridget with “authorisation for her own spiritual motherhood, […] enabl[ing] her to write and speak on behalf of God” (11). By presenting Bridget’s bodily experience of pregnancy as a “vehicle for the female voice and a justification for textual production”, this acts as a powerful reinforcement of the female body (Saetveit Miles 64). For laywomen like Cicely, many of whom would have been mothers, Bridget’s revelation enables them to draw upon their experiences, highlighting that they can use their femininity to connect with Christ’s passion, and therefore enter into an intimate relationship with Christ.

Indeed, iconography from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries frequently focuses on “Saint Anne teaching the Virgin to read”, an image which not only works to naturalise women as readers, but highlights how reading can strengthen female familial relationships (Groag Bell 173). In turn, the Virgin draws upon this by acting as a spiritual mother to Bridget, instructing her on how to lead a virtuous life, and then encouraging her through writing to extend this knowledge out to a wider audience. Through the publication and continental transmission of Bridget’s Revelations, Bridget therefore becomes a spiritual mother to English laywomen like Cicely, who through her matrilineal transmission of Bridget’s book, passed down the knowledge she gained to later female generations.

Beyond the Text: Oral and Ocular Ways of Reading

The varied ways of reading in the medieval period opened up the influence of continental women to a wider section of society. D.H. Green elaborates on these “different ways of reading” (6), stating that the definition of what constitutes reading in this era is broad and nuanced, not simply “visually decoding written signs” (43).These various different ways of reading include: oral ways of reading, applying to “those who ‘read’ with their ears rather than with their eyes” (20), and ocular, such as “reading pictures” (Green 51). Indeed, the English mystic Margery Kempe (1373-1413), was introduced to continental women such as St Elizabeth of Hungary through oral ways of reading. As a result of hearing these works read aloud, this inspired Margery to have her own visionary experiences published. The image of St Bridget of Sweden on the roodscreen in St Andrew’s Church in Kenn (Devon), highlights the liberating effect of ocular ways of reading, enabling illiterate women to map their own narratives onto Bridget’s image. Through these different ways of reading, it can be argued that this provided illiterate women with opportunities to engage with and enter into textual communities.

The Book of Margery Kempe, documents the series of revelations that occurred between Margery Kempe and Christ, highlighting that despite being illiterate “uneducated as she was” (167), Margery had an extensive knowledge of the works of religious women, as her priest read to her “many a good book of high contemplation” (182). Whilst Margery’s status as an illiterate laywoman, can be attributed to”[the] cultural sense at the turn of the fourteenth into the fifteenth century […] that women should not be fully literate” this did not prevent Margery from engaging with these communities of continental religious women and their works (Krug 29). Through hearing about these lives of religious women, Grisé argues that this resulted in Margery aligning “herself with the tradition of holy women from the continent” (HWIP 93). The profound influence of St Bridget of Sweden on Margery has frequently been discussed by scholars such as F.R. Johnston and Nanda Hopenwasser and Signe Wegener; however, there is far less criticism relating to the influential role St Elizabeth had upon Margery, who offered “a model for Margery Kempe’s own contemplative experiences […] [Margery’s] invocation of Elizabeth’s tretys demonstrates pious laity had detailed knowledge of her writings” (101).

Griffith’s statement with its reference to Elizabeth’s works offering “a model for Margery Kempe’s own contemplative experience” provides an opportunity to discuss why this work would have resonated so strongly with Margery, but also with other English medieval women, both religious and lay. The Revelations of St Elizabeth of Hungary centre on a series of revelations between the Virgin Mary and Elizabeth and indeed, Elizabeth’s text was well received amongst medieval women, as it was published by the notable printers Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson (Grisé HWIP 83). Indeed, The Revelations’ foregrounding of the doubts and mistakes Elizabeth makes in her journey towards spiritual fulfilment, documenting how she “in prayeng wepte full bitterly, dredynge that she hadde not fully kepte the forsayd war[n]ynge of the glorious Virgyne” emphasises why her work was so popular amongst medieval women (59). Elizabeth is also described as receiving a stern rebuke from Mary, as a result of being distracted by her teachings due to the presence of another person in the church “O daughter […] that thou art yet a foole and undescrete that aplyent thyn […] herte to any worldly thynges whyle that hast me present wyth thee” (71).

Indeed, it is necessary here to provide some information on the scholarly controversy surrounding the authorship of Elizabeth’s Revelations in order to assess why this text would have appealed to laywomen like Margery. Sarah McNamer in her introduction to The Two Middle English Translations of the Revelations of St Elizabeth of Hungary, provides an extensive overview of the likely candidates for authorship: the Franciscan St Elizabeth, daughter of King Andreas II of Hungary (9), Elizabeth of Schönau, a “Benedictine nun who received revelations” (12) and Elizabeth of Töss, regarded by scholars as the most likely candidate for authorship who was “the daughter of King Andreas III of Hungary and the great-niece of the better -known St Elizabeth” (12). As a public woman, indeed the daughter of a king, experiencing these revelations from Christ and writing about the difficulties she faces, Elizabeth of Töss acts as a relatable figure for women like Margery. For Margery, having to balance spiritual devotion with being a mother to “fourteen children” (Kempe 153), Elizabeth’s Revelations highlight that it is possible for laywomen to receive high spiritual messages from Christ, and that these experiences can be transformed into narratives. By gaining knowledge of Elizabeth’s work through having the Revelations read aloud to her, this draws Margery and other illiterate women closer to Elizabeth who acts as a bond of female reassurance, emphasising that despite tribulations, it is possible for all women to obtain the Christian values of “piety, meekness and obedience” in order to live a virtuous life (McNamer 92).

Margery’s knowledge of the similarities between the affective piety practiced by herself and Elizabeth, noting that Elizabeth “also cried out with a loud voice, as is written in her treatise ” is gained by having these spiritual works read aloud to her (Kempe 193). Margery and Elizabeth’s shared affective piety (an emotional response to the sufferings Christ sustained at His crucifixion),is frequently referenced throughout their texts: Margery is described as “often cry[ing] and roar[ing]” (Kempe 212), and Elizabeth is portrayed as weeping “full bitterly” (McNamer 59). This offers Margery a point of connection, linking together the mysticism practiced by Elizabeth in continental Europe, to influence the life of Margery in Lynn, Norfolk.

Alcuin Blamires states that affective piety was a common feature of medieval religious life, noting that “by the fourteenth century it dominated the lay religious imagination”, but was regarded “as a type of elementary practice suitable for those- including de facto most women […] – whose educational limitations disqualified them from more sophisticated forms of contemplation” (152). In a period where women’s “subordinate position in society removed them from much exercise of authority (intellectual or otherwise)” the affective piety displayed in Margery and Elizabeth’s texts has subversive possibilities, troubling patriarchal expectations surrounding the nature of women’s visionary writing (Green 244). As writing was one of the only means in the period which enabled women to have their experiences heard, Rosalynn Voaden argues that writing had a liberating effect:

“Writing disembodied the word, freeing the prophetic message from its association with woman in all her corporeality and corruption. Rather than an emotional, vernacular flow of words issuing from an orifice in the ‘grotesque’ body of a woman, the Word of God was transmitted through the written corpus, which was, undoubtedly, masculine: sealed, rational and Latinate” (56)

Indeed, Voaden highlights the gendered emphasis of religious writing, but seems to imply that the only way in which women could have their voice heard was to become masculine, ensuring their experiences remained “sealed, rational and Latinate”. However, the affective piety displayed in the mystical texts of Margery and Elizabeth, subverts this, with their loud, uncontained bodily weeping and crying, a far cry from being “sealed, rational”. Green states that despite women’s limited educational opportunities, this was not a setback as “feminine weakness […] could be converted into a sign of her strength (as a vessel for conveying God’s message)” (256). Indeed, this argument can be extended to emphasise how affective piety highlights Margery and Elizabeth’s strength, as they become vessels to experience and preach about Christ’s passion. Rather than internalising their suppression to the patriarchal society, their bodily response of affective piety is an empowering externalisation of their intimate relationship with Christ.

For an illiterate laywoman like Margery, by having these continental women’s visionary experiences read aloud to her, and realising their shared practice of affective piety, it encourages Margery to engage with these textual communities to share her experiences. In the Proem to Margery’s Book, it is revealed that Christ appears in a revelation to Margery, instructing her to write “down her feelings and her revelations, and her form of living, so that His goodness might be known to the world” (Kempe 35). The emphasis on Margery’s text being spread “to the world” highlights the global influence of these continental women documenting their journeys to achieve spiritual fulfilment with Christ, and places Margery within this textual community. However, whilst continental women such as Elizabeth of Hungary, and even illiterate women like Margery were able to have their experiences published, it is important to stress the obstacles women faced in doing so. As stated previously, due to Paul’s injunction that women should remain silent in churches, this prevented women from education. Green states that whilst Paul prohibited women from speaking in churches, he overlooked writing as a form of communication, which “made it possible for their [women’s] teaching to spread much further, to be made public or to be ‘published'” (237).

However, Paul’s oversight on the influence of writing, provided women with a loophole. By claiming that God instructed them to write down their experiences, this enabled women to navigate around the patriarchal system without repercussions, as they were not preaching or teaching the word of God, but were merely a “passive vehicle for her experiences and for the edifying message of God’s love” (Barratt Women’s Writing in Middle English 8). The English mystic Julian of Norwich (c.1342-1416), in her Revelations of Divine Love, constructs herself as a “passive vehicle” to spread God’s message, emphasising not only her inferiority as a woman, but her awareness that she is not prohibited to teach: “God forbid that you should say or assume that I am a teacher, for that is not what I mean […] for I am a woman, ignorant, weak and fail” (of Norwich 10-11).

Margery’s Book describes how she defends herself from clerics who accuse her of preaching, stating that “I do not go into any pulpit. I use only conversation and good words” (164). Indeed, this is only one of the many tribulations that she faced, as Margery’s Book documents in detail the hardships she faced as an illiterate woman to have her story transcribed. Initially enlisting a man who wrote the book so poorly that no-one could understand it “unless it were by special grace” (35), after several more failed attempts, it was completed by a priest who “through the help of God […] is now truly drawn […] this little book” (261). By navigating around the restrictions imposed on women’s writing by the patriarchal society, and by overcoming these scribal difficulties, Margery is able to add her voice to the tradition of these continental women. Therefore, this enables her to become an active participant in adding to this textual tradition of women’s experiences.

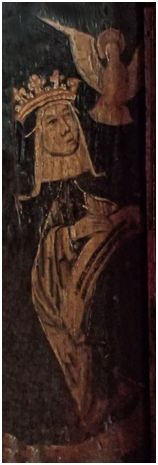

Depictions of continental women in iconography provides a visual connection to their texts. The sixteenth century rood screen in St Andrew’s Church in Kenn, contains forty-four painted panels of saints, amongst them St Bridget of Sweden (Fig.2). Indeed, the presence of the elaborate rood screen in this rural church, highlights the extent in which these female mystics have been absorbed into the everyday life of people in England. It is believed by scholars that Katherine, Countess of Devon (1479-1527), funded the cost of this roodscreen (Griffith 114). However, the significance of this roodscreen becomes more apparent when taking into consideration that Katherine’s grandmother was Cicely, Duchess of York, the same Cicely that bequeathed a copy of St Bridget’s Revelations to Katherine’s cousin, Anne de la Pole (Griffith 115). The presence of St Bridget in Katherine’s funded roodscreen, highlights the central role Bridget played in shaping Cicely’s family textual network, enabling Bridget’s influence to be sustained throughout later female generations. Furthermore, the presence of Bridget on the roodscreen emphasises how Katherine is extending her appreciation of Bridget beyond her family’s textual community, to proactively shape the literate practices of the congregation at Kenn.

Griffith states that Katherine’s sponsorship of the roodscreen highlights the ways in which “the reading habits of the literate laity could influence the devotional life of larger sections of the community” (116). Indeed, it is extremely likely that the majority of the congregation at Kenn would not have been literate, and the screen therefore acts as a signifier for Bridget’s text. By viewing the screen, the congregation would be able to associate this with the knowledge they had concerning Bridget’s life. Furthermore, this act of reflecting upon the images of the rood screen whilst partaking in communal worship, creates a textual community amongst the congregation. The gaze of each member upon the image of Bridget creates a multiplicity of narratives, as the congregation maps their own experiences of how they learned about her life, onto her image. Whilst this may not be a conventional type of textual community in the sense that the congregation have not physically written an account of their experiences with Bridget’s story; however, within the act of parish worship, the presence of continental women in iconography, provides a communal space where the congregation are encouraged, through viewing their images, to create their own stories.

Extending this idea further, it is important to discuss the function and symbolism represented by the roodscreen. Indeed, the function of the screen serves to separate the public congregation from the priests, which is at once paradoxical. With the church as a symbol of community gathering and inclusion, such a spatial barrier creates a sense of isolation and division between the priests and the congregation. The symbolism of a roodscreen can be extended further to act as a metaphor for the treatment of female literacy. Just as the roodscreen represents a barrier between the congregation and the priests, this highlights how women were barred from the formal textual community of clerical reading. This is because it “presented a provocation in its use of the vernacular; and it offered a form of experimental instruction by the uneducated alongside that of Latin theology” (Green 37). However, just as the roodscreen provides the congregation with a glimpse of the priests, whilst at the same time reinforcing these divides, this represents the selective role that women were expected to perform in the literate community. Indeed, women were expected to participate in the literate community simply for didactic purposes, namely the education of their children, as “Christian moralists repeatedly declared that it was women’s duty to concern themselves with the literary and moral upbringing of their children” (Groag Bell 162).

The variety of literate practices in the medieval period played an important role in spreading the influence of continental women out to a wider audience. In the case of Margery Kempe, by having texts of continental women read aloud to her, this enabled Margery to gain access to the continental mystical tradition, influencing her piety and inspiring her to publish her own visionary experiences. The image of St Bridget of Sweden on the roodscreen at St Andrew’s Church, emphasises how the aristocracy played an active role in introducing illiterate members of the congregation to continental women. Through the combination of these different ways of reading, this enabled illiterate women to gain knowledge of these continental women who navigated their confined role in the patriarchal society in order to share their visionary stories. Fundamentally, this enabled women to gain access to textual communities.

Conclusion

Indeed, it can be argued that continental women had a significant influence on the literate practices of English medieval women, through cultivating textual communities and providing both religious and laywomen alike with guidance on how to achieve spiritual fulfilment. The Bridgettine Order of Syon Abbey highlights the influential role continental women played in establishing its international reputation as a religious textual community. Most significantly, the network of books commissioned for the Abbey, such as Catherine of Siena’s The Orcherd of Syon, emphasises how continental women took an active role in shaping the spirituality of English medieval women. In The Orcherd of Syon organic imagery in the form of the “frutyful orcherd” (1), reinforces the values needed to cultivate a fruitful religious community, stressing how individual spiritual growth feeds into and sustains the community. The use of flourishing imagery also serves as a metaphor for the growth of Syon Abbey’s textual network, thereby spreading the works of continental women to the wider community.

The circulation of continental women’s texts amongst female readers in England also illuminates the increased interaction between female lay and religious communities. Lady Margaret Beaufort was one of the driving influences behind this increased engagement, commissioning William Caxton to publish the Bridget attributed Fifteen Oes. Indeed, by extending these Syon commissioned texts out into the wider community, this worked to make “the fruits of monastic life available to laity” (Lee 164). The influence of St Bridget of Sweden upon Cicely, Duchess of York highlights how continental women were absorbed from their religious context into the domestic lay household, in order to serve each individual laywoman’s purpose. Cicely’s emulation of Bridget’s lifestyle highlights laywomen’s “conscious appetite for forms of quasi-monastic piety inspired in large part by the Bridgettine tradition itself” (Jones and Walsham 15). Cicely’s request to have the works of continental women read to her whilst she dined with her gentlewomen emphasises the female textual community in action. Upon her death, Cicely’s bequest of her copy of St Bridget’s Revelations to her granddaughter Anne de la Pole, highlights Bridget’s significant role in fostering a “matrilineal literary tradition” (Groag Bell 179). Indeed, Anne later became a prioress at Syon Abbey, emphasising how her grandmother’s admiration of Bridget was passed onto her, thereby actively shaping the piety of later female generations.

The role of the aristocratic laity in drawing upon continental women to influence the devotion and literate practices of illiterate women, is emphasised through the depiction of St Bridget of Sweden on the roodscreen in St Andrew’s Church, Kenn. Despite being unable to read, the presence of Bridget on the roodscreen enabled these women to engage with textual communities, mapping their own stories of her onto the image. Through the image of Bridget, this works again to emphasise how continental women served not only as symbols of inclusion but also as a visual symbol of the success with which they navigated around the repressive patriarchal system.

The publication of Margery Kempe’s visionary experiences highlights that despite being illiterate, Margery was still able to enter into the textual community of female mysticism. Despite the emphasis on the troubles she faced in enlisting a scribe to write down her story, nevertheless the resilience of Margery illustrates the significant influence of continental visionary writers upon her. Indeed, The Book of Margery Kempe foregrounds the controversy Margery was subjected to from clerics due to navigating around the patriarchal system. However, this then raises wider question surrounding the nature of female visionary writers’ work, and the content within them that resonated so strongly with English medieval women.

As examples of the mystical tradition, these continental texts display strong didactic elements, to highlight to the reader the values needed to achieve spiritual fulfilment. By attaching Christian values to organic and domestic imagery, the texts locate the journey for spiritual fulfilment within the world of the familiar. In The Orcherd of Syon the image of humanity labouring “in þe vyneȝerd of holy chirche” (63), has associations of nourishment, with the female nuns at Syon working interdependently to help each other in their journey to live a virtuous Christian life. Unlike The Orcherd of Syon, in her Revelations St Bridget adopts the discourse of motherhood to act as a spiritual mother for English medieval women. The emphasis on Bridget’s family struggles and the tensions she faced balancing her role as a mother with her spiritual worship, makes her extremely relatable for laywomen like Cicely. Indeed, in the Revelations the Virgin acts as a female role model to emphasise the importance of the female body in worshipping Christ. By drawing upon discourses of pregnancy, this highlights to medieval women that they too can draw upon their own femininity to enter into an intimate relationship with Christ. This idea of the gendered nature of worship is emphasised through Margery Kempe’s adoption of affective piety, which is practised by St Elizabeth of Hungary in her Revelations. Through the bodily worship of affective piety, St Elizabeth of Hungary opens up the contained female body to emphasise its importance in worshipping Christ. This idea can be extended further to argue that through the use of affective piety, this acts as a powerful reaction against the repressive patriarchal society.

It has been the aim of this dissertation to emphasise the active role continental women played in shaping the literate practices of English medieval women. Through cultivating textual communities, this helped foster female to female relationships on a family level; however, on a wider scale, this facilitated the movement from exclusive to inclusive communities. The actions of Lady Margaret Beaufort in publishing these continental mystical texts from the community of the convent and circulating them out to laywomen, highlights the importance of continental women in facilitating engagement between lay and religious communities. By drawing upon examples of visionary writers, female book owners and iconography, I have aimed to emphasise the variety and scope of the networks continental women helped cultivate. Despite the broad outlook of this dissertation, this is by no means the final chapter in the active critical debate surrounding the influence of continental women upon English medieval women.

Works Cited

Armstrong, C.A.J. “The Piety of Cicely, Duchess of York: A Study in Late Mediaeval Culture.” For Hilaire Belloc: Essays in Honour of His 72nd Birthday. Ed. Douglas Woodruff. London: Sheed and Ward, 1942. 73-94. Print.

Bainbridge, Virginia R. “Syon Abbey: Women and Learning c.1415-1600.” Syon Abbey and its Books: Reading, Writing and Religion c.1400-1700. Ed. E.A. Jones and Alexandra Walsham. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2010. 82-103. Print.

Barratt, Alexandra. “Continental Women Mystics and English Readers.” The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing. Ed. Carolyn Dinshaw and David Wallace. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. 240-255. Print.

—Women’s Writing in Middle English. 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman/Pearson, 2010. Print.

Bell, David N. What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval English Nunneries. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1995. Print.

Blamires, Alcuin. “Beneath the Pulpit.” The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing. Ed. Carolyn Dinshaw and David Wallace. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. 141-158. Print.

Despres, Denise L. “Ecstatic Reading and Missionary Mysticism: The Orcherd of Syon.” Prophets Abroad: The Reception of Continental Holy Women in Late-Medieval England. Ed. Rosalynn Voaden. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1996. 141-160. Print.

Erler, Mary C. Women, Reading and Piety in Late Medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Fifteen Oes. Westminster: William Caxton, 1491. Historical Texts. Web. 9 April 2016.

Figure 1. St Catherine of Siena surrounded by twelve nuns, woodcut, from Wynkyn de Worde, Here begynneth the orcharde of Syon in the which is conteyned the reuelacyons of seynt [sic] Katheryne of Sene, with ghostly fruytes [and] precyous plantes for the helthe of mannes soule (London, 1519); rpt. in Syon Abbey and its Books: Reading, Writing and Religion c.1400-1700. Ed. E.A. Jones and Alexandra Walsham. (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2010; print; 32).

Figure 2. Painted panel of St Bridget of Sweden from the sixteenth century roodscreen in St Andrew’s Church, Kenn. 16th century. Painted wood panel. St Andrew’s Church Kenn, Devon.

Green D.H. Women Readers in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

Griffith, David. “The Reception of Continental Women Mystics in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century England: Some Artistic Evidence.” The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England: Exeter Symposium VII: Papers Read at Charney Manor, July 2004. Ed. E.A. Jones. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2004. 97-117. Print.

Grisé, C. Annette. “Holy Women in Print: Continental Female Mystics and the English Mystical Tradition.” The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England: Exeter Symposium VII: Papers Read at Charney Manor, July 2004. Ed. E.A. Jones. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2004. 83-95. Print.

—“‘In the Blessid Vyneȝerd of Oure Holy Saueour’: Female Religious Readers and Textual Reception in the Myroure of Oure Ladye and The Orcherd of Syon.” The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England, Ireland and Wales: Exeter Symposium VI: Papers Read at Charney Manor, July 1999. Ed. Marion Glasscoe. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1999. 193-212. Print.

— ‘Moche profitable unto religious persones, gathered by a brother of Syon’: Syon Abbey and English Books.” Syon Abbey and its Books: Reading, Writing and Religion c.1400-1700. Ed. E.A. Jones and Alexandra Walsham. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2010. 129-154. Print.

Groag Bell, Susan. “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture.” Women and Power in the Middle Ages. Eds. Mary Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski. Athens, Ga.; London: University of Georgia Press, 1988. 149-187. Print.

Hodgson, Phyllis and Gabriel M. Liegey. The Orcherd of Syon: Volume I: Text. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1966. Print.

Hogg, James. The Rewyll of Seynt Sauioure and A Ladder of Foure Ronges by the which men mowe clyme to Heaven: edited from the MSS. Cambridge University Library Ff. 6.33 and London Guildhall 25524. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, 2003. Print.

Hopenwasser, Nanda and Signe Wegener. “Vox Matris: The Influence of St Birgitta’s Revelations on The Book of Margery Kempe: St Birgitta and Margery Kempe as Wives and Mothers.” Crossing the Bridge: Comparative Essays on Medieval European and Heian Japanese Women Writers. Ed. Cynthia Ho and Barbara Stevenson. New York: Palgrave, 2000. 61-85. Print.

Hutchinson, Ann M. “Reflections on Aspects of the Spiritual Impact of St Birgitta, The Revelations and the Bridgettine Order in Late Medieval England.“ The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England: Exeter Symposium VII: Papers Read at Charney Manor, July 2004. Ed. E.A. Jones. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2004. 69-82. Print.

— “Reviewed Work: The Liber Celestis of St Bridget of Sweden. The Middle English Version in British Library MS Claudius BI, together with a life of the saint from the same manuscript. Volume I, Text. The Early English Text Society, No. 291 by Roger Ellis” Mystics Quarterly. 16.4 (1990): 217-219. JSTOR. Web. 2 April 2016.

Johnston, F.R. “The English Cult of St Bridget of Sweden.” Analecta Bollandiana: Revue Critique D’Hagiographie. 103.1-2 (1985): 75-93. Print.

Jones, E.A. and Alexandra Walsham. “Syon Abbey and its Books: Origins, Influences and Transitions.” Introduction. Syon Abbey and its Books: Reading, Writing and Religion c.1400-1700. Ed. E.A. Jones and Alexandra Walsham. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2010. 1-38. Print.

Kempe, Margery. The Book of Margery Kempe. Trans. Barry Windeatt. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985. Print

Krug, Rebecca. Reading Families: Women’s Literate Practice in Late Medieval England. Ithaca NY; London: Cornell UP, 2002. Print.

McNamer, Sarah. The two Middle English translations of the Revelations of St Elizabeth of Hungary : ed. from Cambridge University Library MS Hh.i. 11 and Wynkyn de Worde’s printed text of ?1493. Heidelberg : Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1996. Print.

Miles, Laura Saetveit. “Looking in the Past for a Discourse of Motherhood: Birgitta of Sweden and Julia Kristeva.” Medieval Feminist Forum: Journal of the Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship. 47.1 (2011): 52-76. University of Iowa Libraries’ Institutional Repository. Web. 15. April 2016.

of Norwich, Julian. Revelations of Divine Love. Trans. Elizabeth Spearing. London: Penguin, 1998. Print.

Power, Eileen. Medieval English Nunneries. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1922. Print.

Riddy, Felicity. “‘Women talking about the things of God’: a late medieval sub-culture.” Women and Literature in Britain,1100-1500. Ed. Carol M. Meale. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993. 104-127. Print.

Searby, Denis and Bridget Morris. The Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden: Volume I: Liber Caelestis, Books I-III. Trans. Denis Searby. Ed. Bridget Morris. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. Print.

—The Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden: Volume III: Liber Caelestis, Books VI-VII. Trans. Denis Searby. Ed. Bridget Morris. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

Stock, Brian. The Implications of Literacy: Written Language and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983. Print.

The Bible. Introd. and notes by Robert Carroll and Stephen Pickett. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print. Oxford World’s Classics. Authorized King James Vers.

Voaden, Rosalynn. “God’s Almighty Hand: Women Co-Writing the Book.” Women, the Book and the Godly: Selected Proceedings of The St Hilda’s Conference, 1993: Volume I. Ed. Lesley Smith and Jane H.M.Taylor. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1995. 55-65. Print.