Records from the Anglo-Saxon period largely depict the deeds of men, from the military successes of King Alfred the Great to the piety of Edward the Confessor. Yet, at a time when women were seen almost as commodities – whether as tools to strengthen political unions or child bearers – some managed to wield considerable power. In the monastic world, women became abbesses, and transformed their communities into intellectual powerhouses, while others were skilled royal rulers. Here, discover the lives of some of the era’s most influential women.

Aethelflaed

An astute leader, military strategist and mother, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians was one of England’s greatest queens, but today, her accomplishments remain largely unknown. In his twelfth-century Historia Anglorum (The History of the English People), the historian, Henry of Huntington, described Aethelflaed as being “more illustrious than Caesar,” and the historian, William of Malmesbury stated that she “ought not to be forgotten.”

Little is known about her childhood, but she was born into one of the era’s most illustrious households. Her father, Alfred the Great (the King of Wessex), achieved lasting acclaim for his educational reforms and martial prowess, and her nephew, Athelstan, later became the first king of England. Believed to have been born in the late 9th century, Aethelflaed was married at 16 to Aethelred, Lord of Mercia; however, she wanted to extend her influence outside of the court.

Aethelflaed grew up in a time of turbulence. During her early years, the Vikings had conquered lands across the major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – with the exception of Wessex. Her marriage to Aethelred united Mercia and Wessex, and the kingdoms worked to resist Viking invaders.

In the years leading up to Aethelred’s death, Aethelflaed established herself as a commanding ruler. She made diplomatic arrangements with the Vikings, and worked tirelessly to oppose their attacks. In 910, she defeated Viking troops at Tettenhall (modern-day Wolverhampton), who had lain waste to much of Mercia. Aethelflaed was hailed as a warrior queen, and upon Aethelred’s death in 911, she became the sole ruler of the kingdom.

In the following years, Aethelflaed continued to oppose the Vikings. In 917, she re-conquered the Viking-held city of Derby, and liberated the city of Leicester in 918. Aethelflaed died on 12 June 918, and was buried at St Oswald’s Priory in Gloucester. During her lifetime, she had transformed this region by returning the body of St Oswald to Mercian land.

A pioneering ruler, Aethelflaed laid the foundations for modern-day England. 2018 marks the 1100th anniversary of her death, and hopefully, her achievements will inspire generations to come.

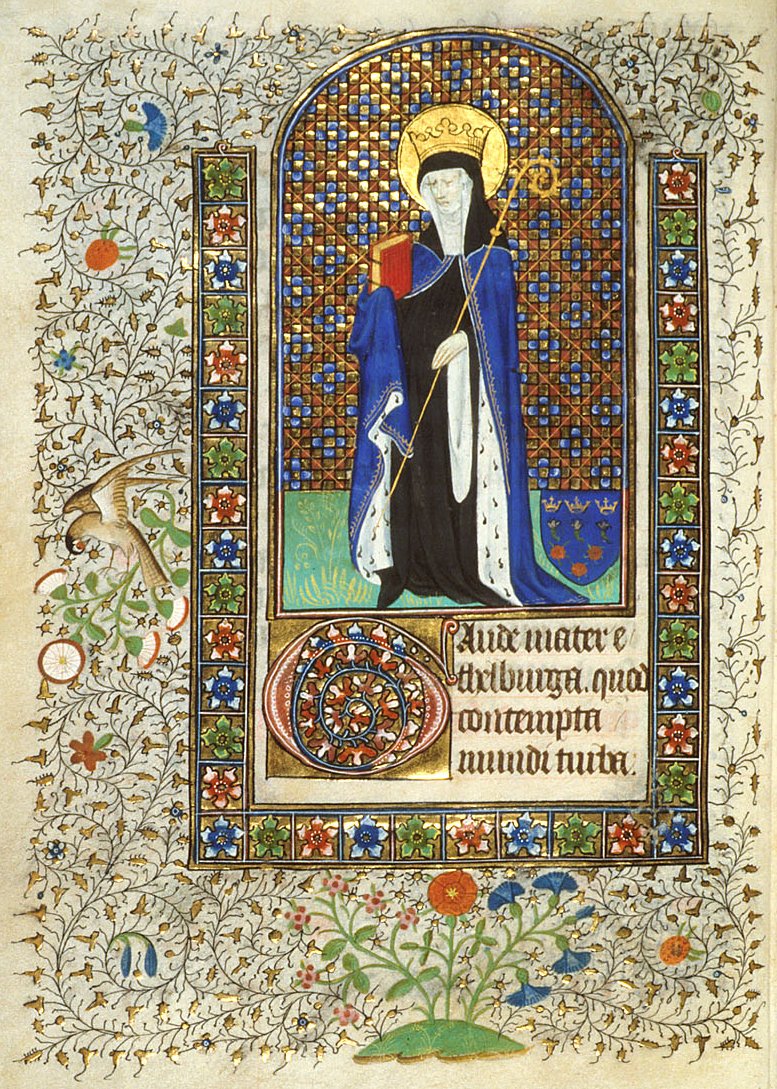

St Ethelburga of Barking (Aethelburh)

The first leader of a monastic order for women in England, St Ethelburga was admired for her benevolence and heroism. A strong-willed character, St Ethelburga was banished to a nunnery by her brother, St Earconwald, after refusing to marry a pagan prince. However, this action would determine her life’s purpose. Impressed by St Ethelburga’s leadership abilities, St Earconwald founded Barking Abbey in Essex for her in the mid-seventh century. As abbess of this double monastery – a centre for both men and women – St Ethelburga was expected to provide soldiers to the king during wartime.

In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede, the Father of English History, describes St Ethelburga’s compassion: “when she had undertaken the rule of this monastery, she proved herself worthy in all things of her brother the bishop, both by her own holy life and by her sound and devoted care for those who were under her rule.”

In 664, a virulent outbreak of the plague spread throughout the monastery. Many of the community died, including St Ethelburga, in 675. Bede explains that: “none who knew her can doubt that, as she departed this life, the gates of her heavenly country were opened for her.”

Barking Abbey continued to flourish after St Ethelburga’s death, and it became an important intellectual centre. Authors including Aldhelm and Goscelin composed works for the Barking nuns. The Abbey’s own St Clemence of Barking (c. 1163-1200) wrote a Life of St Catherine. St Clemence is believed to be England’s first female author, and her work made St Catherine of Alexandria accessible for a medieval audience. By the time of the Dissolution in the 16th century, Barking Abbey was the third richest nunnery in England.

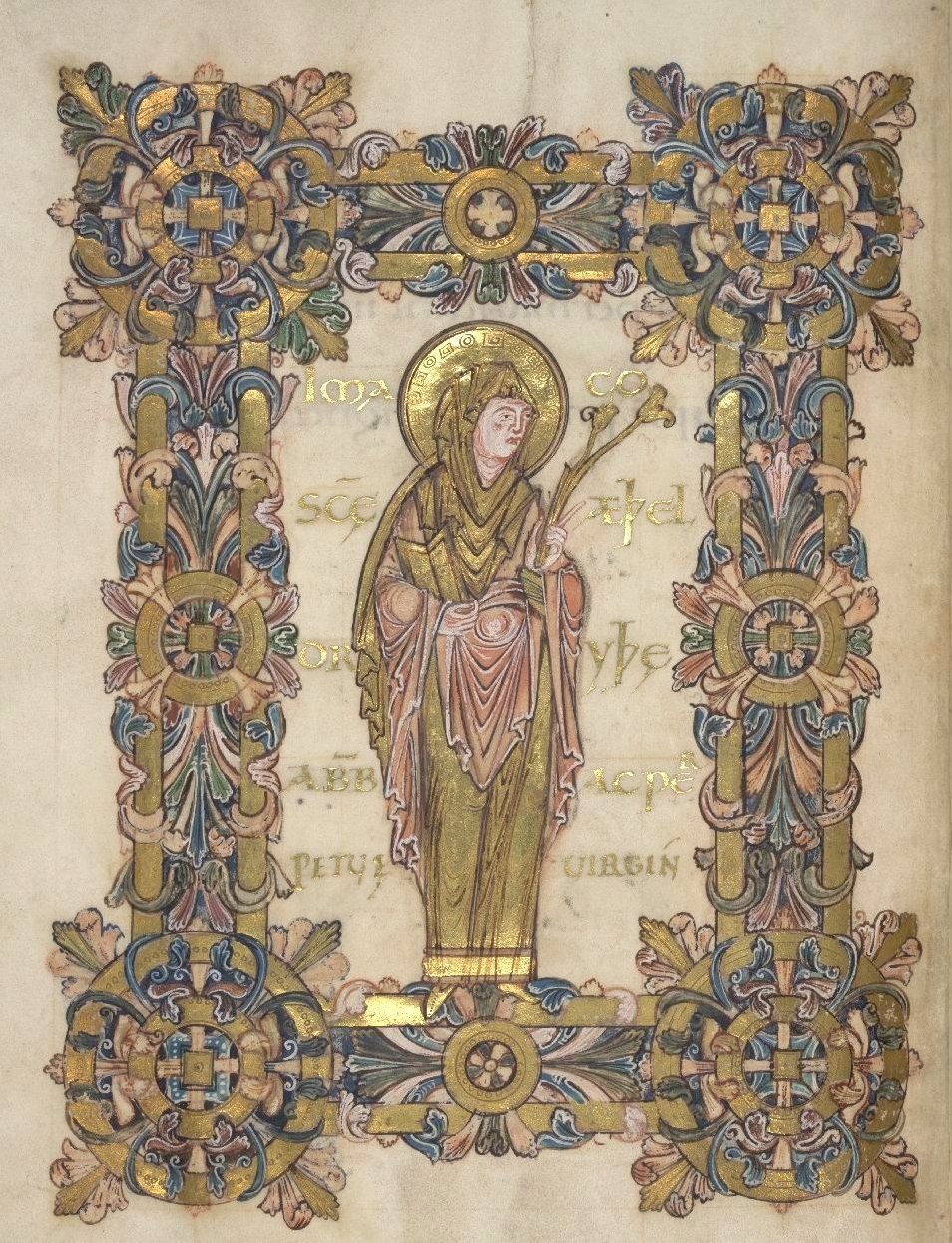

St Hilda of Whitby

Arguably the most famous Anglo-Saxon woman, St Hilda of Whitby was instrumental in developing English Christianity. Like Aethelflaed, St Hilda was born into royalty. A member of the royal household of Northumbria, Hilda was surrounded by powerful leaders: her great-uncle, Edwin, king of Northumbria, was one of England’s most commanding rulers.

But, St Hilda’s early years were filled with turbulence. After the murder of her father, St Hilda and her mother were taken in by Edwin, who raised the young girl within the pagan royal court. During this time, two traditions of Christianity – the Celtic Christians from Ireland and the Roman Christians from Italy – began to spread across the country. In 627, St Hilda and Edwin were baptised by Paulinus of York, a Roman missionary who assisted St Augustine in his conversion of England. Despite being baptised in the Roman tradition, St Hilda became inspired by the teachings of the Irish monk, St Aidan, Bishop of Lindisfarne.

Little is known about St Hilda’s early adulthood, but she became a nun at the age of 33. A natural leader, she quickly became bishop of Hartlepool, before founding the double monastery at Whitby in c.657. One of the most important religious centres in the Anglo-Saxon world, the monastery hosted a variety of activities, both religious and secular. Women would have been involved in crafts including spinning, sewing and weaving, along with reading and writing, while men would have taken part in skills such as metalworking and glass making.

Under St Hilda’s direction, many of Whitby’s community became esteemed ecclesiastical figures. Several of her monks became bishops, and she discovered the literary talents of Caedmon – the first English poet. Caedmon’s Hymn is the oldest Old English poem to survive in manuscript form, and is featured below:

“Now we must praise the Guardian of Heaven

The might of the Lord and His purpose of mind

The work of the Glorious Father; for He,

God, Eternal, established each wonder,

He, Holy Creator, first fashioned

Heaven as a roof for the sons of men.

Then the Guardian of Mankind adorned

This middle-earth below, the world for men,

Everlasting Lord, Almighty King”

(From The Anglo-Saxon World: An Anthology. Translated by Kevin Crossley-Holland)

In 664, St Hilda took part in a landmark event at Whitby, which shaped the course of English Christianity. The Synod of Whitby saw religious leaders from across England come together to discuss matters including the date of Easter, which was celebrated at different times by Celtic and Roman Christians. After lengthy discussion, the decision was made to observe the Roman Christian date.

During her lifetime, St Hilda was a respected monastic ruler. In his Ecclesiastical History, Bede notes: “so great was her prudence that not only ordinary people but also kings and princes sometimes sought and received her counsel when in difficulties.” Following a protracted illness, St Hilda died in 680, and was buried at Whitby. Today, St Hilda’s legacy continues to live on: her name was given to St Hilda’s College, Oxford University, and she became the patron saint of 14 medieval churches.

Aethelburh of Kent

St Hilda’s great-aunt, Aethelburh of Kent, played a crucial role in the development of English Christianity. Her marriage to Edwin, king of Northumbria, facilitated the growth of St Augustine’s Christian mission across the north of the country. However, there were some initial complications. Bede describes how Eadbald, Aethelburh’s brother, refused Edwin’s marriage request, on the grounds that “it was not lawful for a Christian maiden to be given in marriage to a heathen.”

Edwin converted to Christianity, but was killed in battle in 633. After Edwin’s death, Aethelburh returned to Kent, where she founded a double monastery at Lyminge. This was one of the first Benedictine monasteries in England, and contained a rare banqueting hall. Aethelburh died in around 647, but her monastic community continued for nearly two centuries afterwards.

Aethelthryth of Ely (Etheldreda)

Renowned for her devotion – and the miracles she performed after her death – Aethelthryth of Ely displayed her piety from an early age. When Aethelthryth married the ealdorman Tondberht in around 652, she continued to remain a virgin. Upon his death in c.655, she moved to the Isle of Ely, and was soon married to Egfrith, the king of Northumbria. Aethelthryth insisted on preserving her virginity, and Egfrith complied with her request.

Twelve years later, Egfrith wished to consummate their relationship, but Aethelthryth refused. Eager to begin a new life, Aethelthryth left Egfrith, and became a nun in the abbey of Coldingham. A year later, Aethelthryth returned to Ely, and founded a double monastery on the site of the present-day Ely Cathedral.

In around 680, Aethelthryth died from the plague; however, reports spread that she died from a tumour on her neck, as a divine punishment for wearing necklaces. But, after her death, a series of miracles began to occur. When her body was exhumed a few years later, it was found to be perfectly intact. Then, when her tomb was moved, her voice was heard to cry out: “Glory be to the name of the Lord!” Bede describes how her clothes were used to expel devils from individuals, and how her original coffin helped to treat eye conditions.

For two hundred years after Aethelthryth’s death, her monastery continued to thrive, until it was destroyed by the Danes. In 970, Ely was re-founded as a Benedictine community, and it became the most prosperous abbey in England. Aethelthryth became a popular subject for medieval writers, and vast numbers of pilgrims flocked to her shrine. Struck by her piety and humility, Bede even composed a hymn to her, an extract of which is outlined below:

“Of royal blood she sprang, but nobler far

God’s service found than pride of royal blood.

Proud is she, queening it on earthly throne;

In heaven established far more proud is she.”

(From Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Oxford World’s Classics. Translated by Bertram Colgrave, by Judith McClure and Roger Collins)

Find out about Early Medieval Women’s Writing in my interview with Professor Diane Watt here. For Anglo-Saxon literature recommendations, check out my blog post here.