From Starbucks’s unicorn frapuccinos to unicorn beauty products, the mythical creature dominates popular culture. But, the sparkling and gentle animal that is portrayed today is a far cry from its earlier depictions.

Ancient origins

The first reference to the unicorn occurs 2,500 years ago in the work Indica, written by the Greek physician, Ctesias. A combination of geography, zoology and botany, this 4th century BC work is filled with descriptions of exotic places and animals, and includes an account of a strange one-horned creature:

“there are in India certain wild asses which are as large as horses, and larger. Their bodies are white, their horns dark red, and their eyes dark blue.”

Ctesias’s “wild asses” have long fascinated scholars. Several possibilities as to the identity of his animal have been suggested, which include an Indian rhinoceros, a Tibetan antelope and a kiang – an Asian wild ass. But, this elusive creature continued to captivate ancient thinkers. Many centuries later, the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (AD 23-79) emphasised the ferocity of the magical creature in his Natural History:

“[it] has a deep bellow, and a single black horn three feet long projecting from the middle of the forehead. This animal, they say, cannot be taken alive.”

With their emphasis on the unicorn’s power and captivating character, these ancient accounts instigated what were to become defining aspects of unicorn lore. But, overtime, these legends continued to develop. By the medieval period, the unicorn was associated with a range of symbolic meanings. A Christian emblem, a symbol of strength, a hallmark of heraldry – the mythical creature certainly captured the popular imagination. From medieval bestiaries to Books of Hours, these manuscripts below illustrate the creature’s varied representations.

Unicorns and medieval bestiaries

Filled with descriptions of real and imaginary beasts, bestiaries rose in popularity during the late twelfth and the mid thirteenth centuries. These often contained elaborate illustrations of animals, along with text that described their physical and moral qualities. For medieval readers, bestiaries helped to reinforce the notion that the natural world was created by God to instruct humanity.

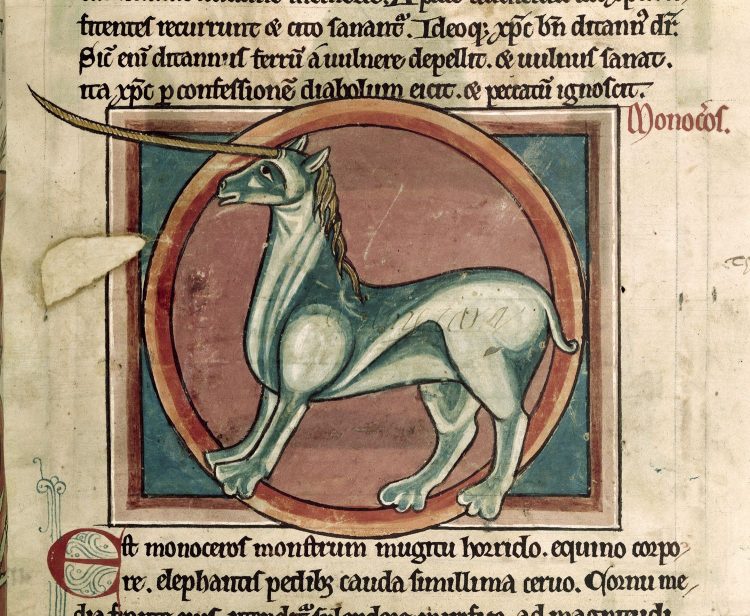

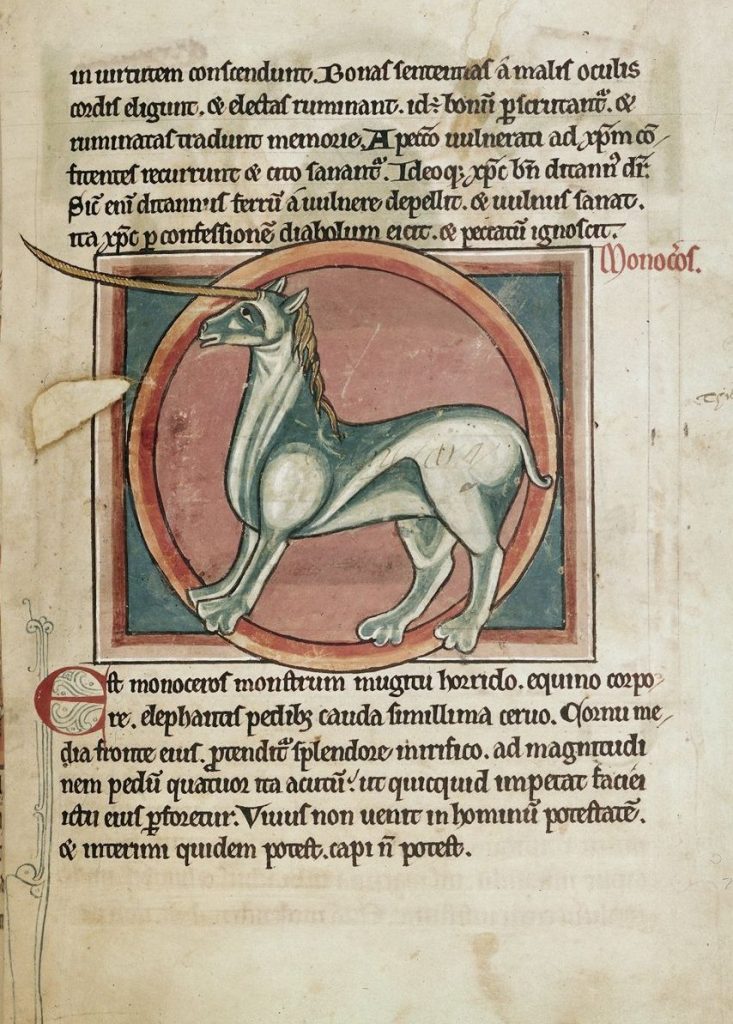

This lavish illustration of a unicorn comes from a 13th century bestiary in Salisbury, England. Below the image, the text contains the word “monocerus.” A monocerus was a ferocious one-horned beast, which, depending on the source, was either interchangeable with a unicorn, or regarded as a separate beast. Written in Latin, this work contains a fascinating array of animals, from antelopes and panthers to griffins and phoenixes.

Unicorns and Christianity

The Bible contains several references to unicorns (although this does depend on the translation). In several instances, the creature serves as a metaphor for strength and ferocity, as illustrated in Numbers 24:8: “God brought them out of Egypt; he hath as it were the strength of the unicorn,” and Deuteronomy 33:17: “His glory is like the firstling of his bullock, and his horns are the horns of unicorns: with them he shall push the people together to the ends of the earth.”

In the above illustration from a 14th century French manuscript, God introduces Adam to Eve in the Garden of Eden. The trio are surrounded by a group of angels and animals, including a unicorn. The 4th century theologian, Bishop Ambrose of Milan, was one of the first thinkers to associate the unicorn with Christ. He famously remarked: “Who is this unicorn, but God’s only son? The only word of God who has been close to God from the beginning!” The image of God, the unicorn and the Garden of Eden, soon became a popular motif for generations of artists and writers.

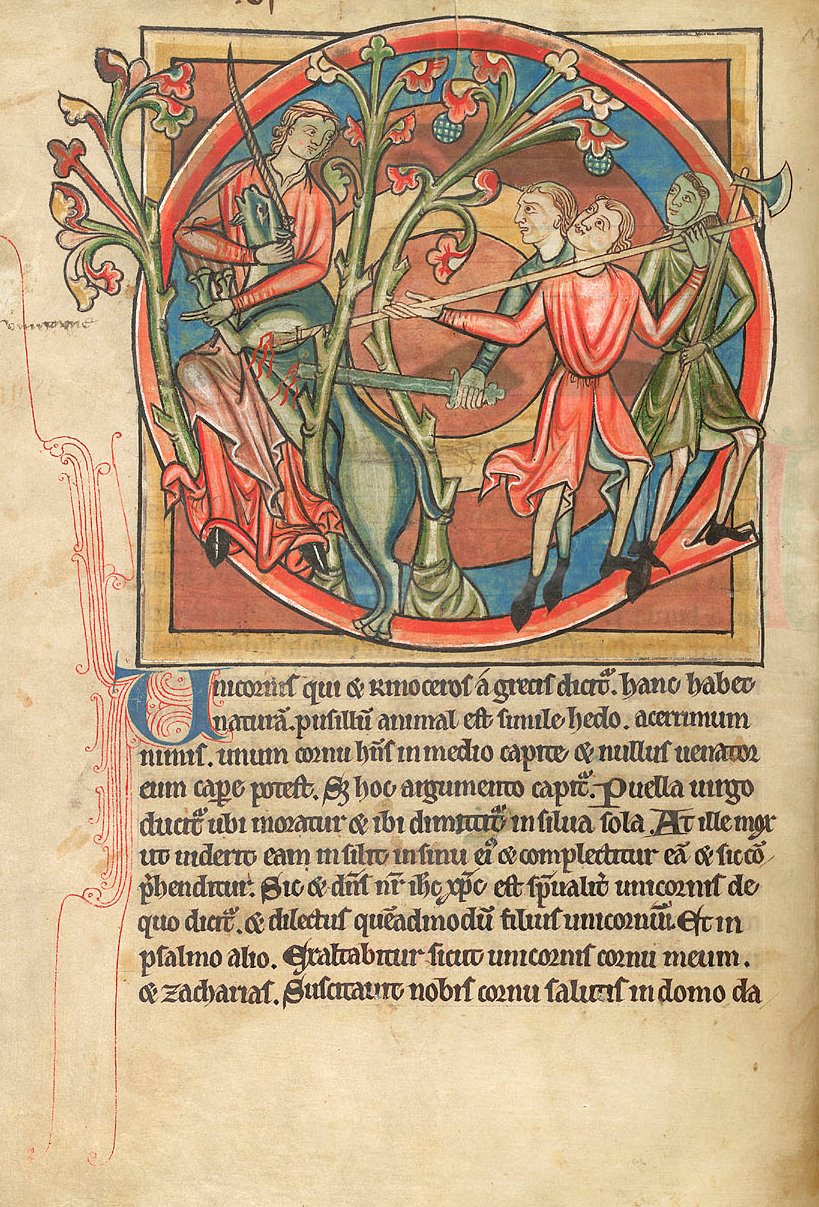

Many medieval texts drew upon the idea of the unicorn as a symbol of Christ. In the British Library’s Harley 4751 manuscript, three men attack a unicorn while it rests in a maiden’s arms. The unicorn’s slaughter by the hunters evokes the Crucifixion, while the maiden symbolises Mary, in whose womb Christ becomes incarnate.

Unicorns and virgins

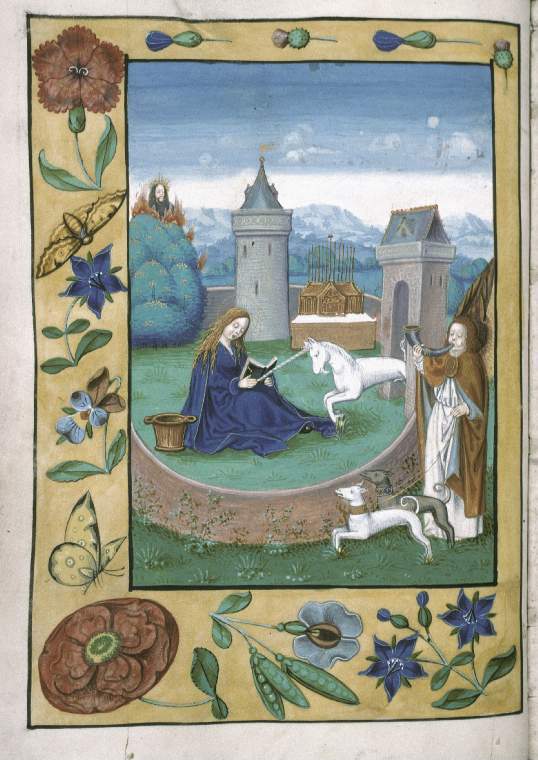

In illustrations throughout the medieval period, unicorns are frequently depicted with virgin girls. This 16th century manuscript comes from a Flemish Book of Hours and marks the Annunciation: the moment when the Angel Gabriel revealed to Mary that she would become the mother of Jesus Christ. A Book of Hours was a collection of Christian prayers, which were meant to be read at different times throughout the day. In this illustration, the Virgin Mary is reading in a walled garden, and a unicorn is resting its head in her lap. The wall around the garden acts as a symbol of her virginity.

However, virgins could also prove detrimental to the one-horned beast. Because of their strength and speed, unicorns were incredibly difficult for hunters to catch – unless they had the help of a virgin. Unicorn legends state that if a virgin was placed in the unicorn’s path, the creature would rest its head in her lap and fall asleep, making it an easy target for the hunter. This gruesome illustration from a thirteenth-century bestiary in Rochester, England, shows this method in action.

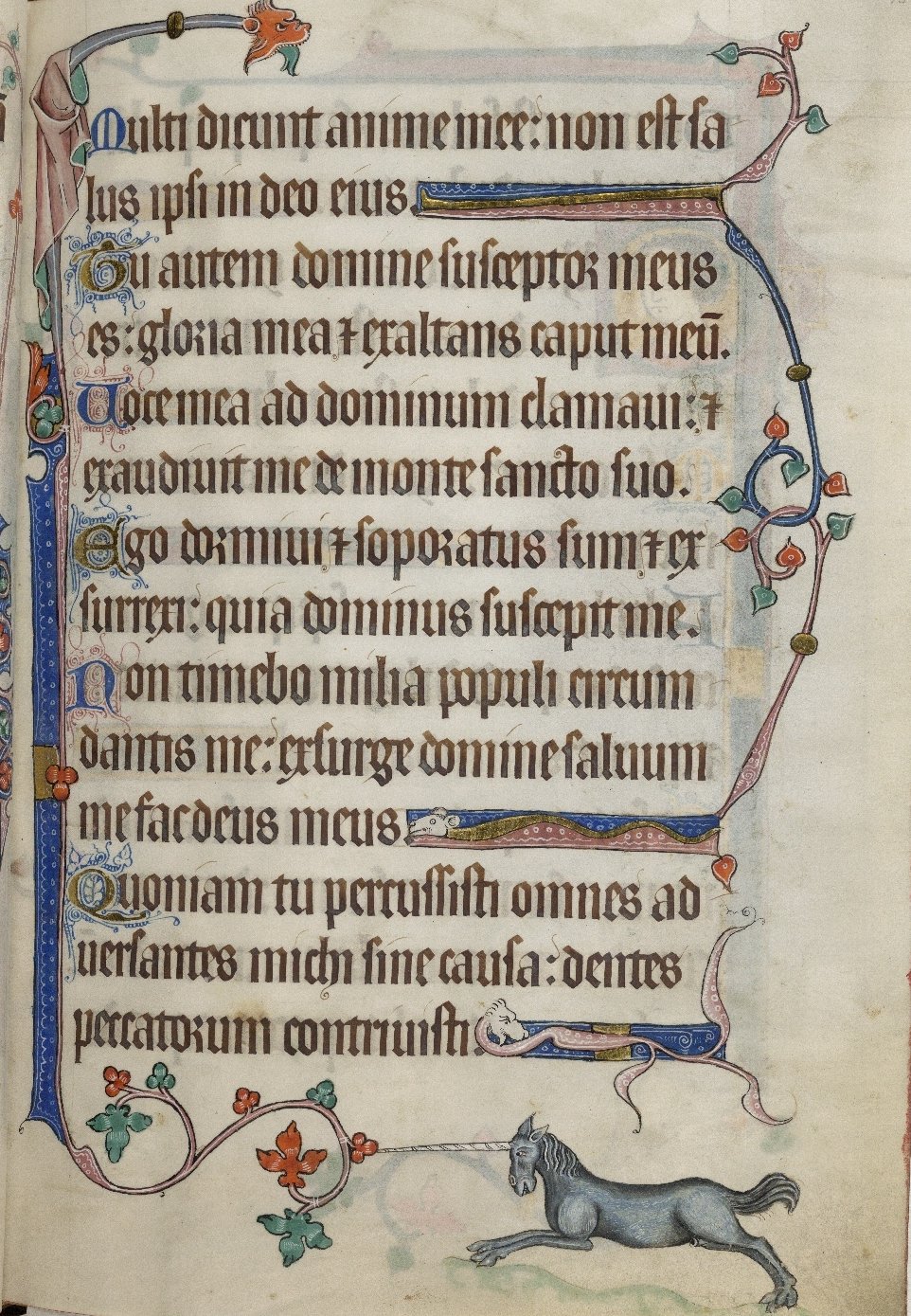

Marginalia marvels

A cultural symbol of the Middle Ages, unicorns often appeared in the margins of books of worship. In this illustration from the Luttrell Psalter, a unicorn and other hybrid creatures adorn the page. Commissioned in the 14th century, the work contains a collection of 150 ancient songs, known as psalms, and is decorated with scenes of everyday life.

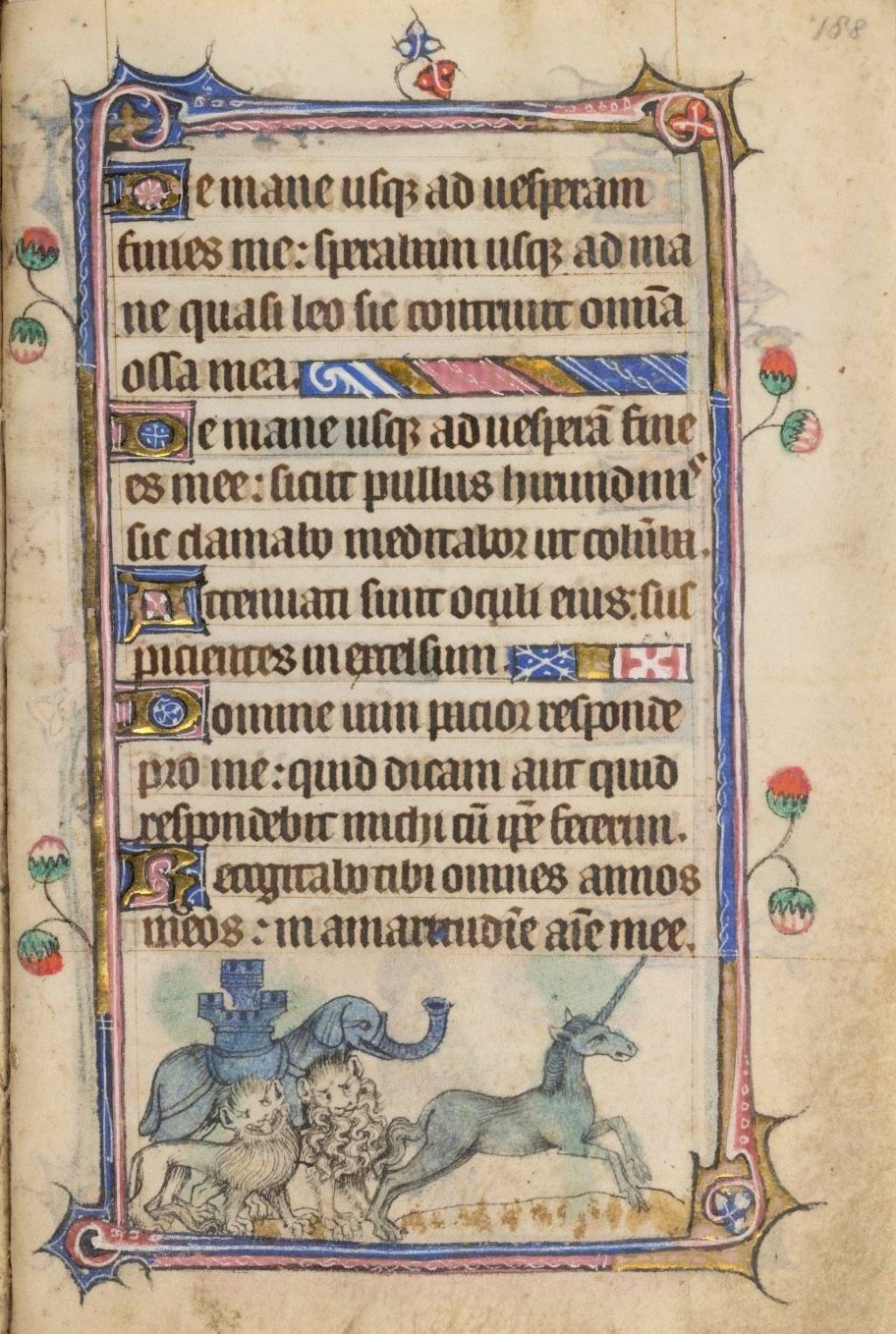

In the ‘Taymouth Hours’ a 14th century book of hours, an illustration of a unicorn appears alongside an elephant and castle. According to legend, the one-horned creature and the elephant were bitter enemies. During fights, the unicorn wounded the elephant by driving its horn into the mammal’s stomach.