For more than 70 years, Penguin Classics have adorned the shelves of bibliophiles across the world. From the tales of Ancient Mesopotamia to the poetry of World War One, the series brings together the best of classic literature. But with so many works to discover, it can be hard to know where to begin.

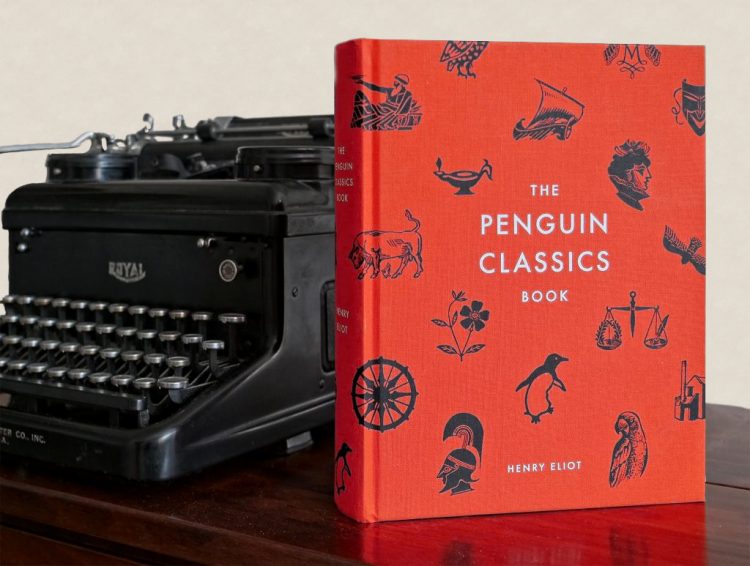

Eager to help people explore the list, Henry Eliot, Creative Editor of Penguin Classics, has published The Penguin Classics Book, a reader’s companion of classic literature. Featuring authors including Aristophanes, Austen, Dante and Dickens, the book reveals the stories behind the series’ 1,200 titles. From the author who thought he was a werewolf to a little-known Vietnamese epic, I talk to Henry about writing The Penguin Classics Book, commissioning new classics, and diversifying the list.

From Ancient Hebrew texts to scientific treatises, the Penguin Classics list covers a variety of genres, regions and languages. How does The Penguin Classics Book help readers to engage with the series?

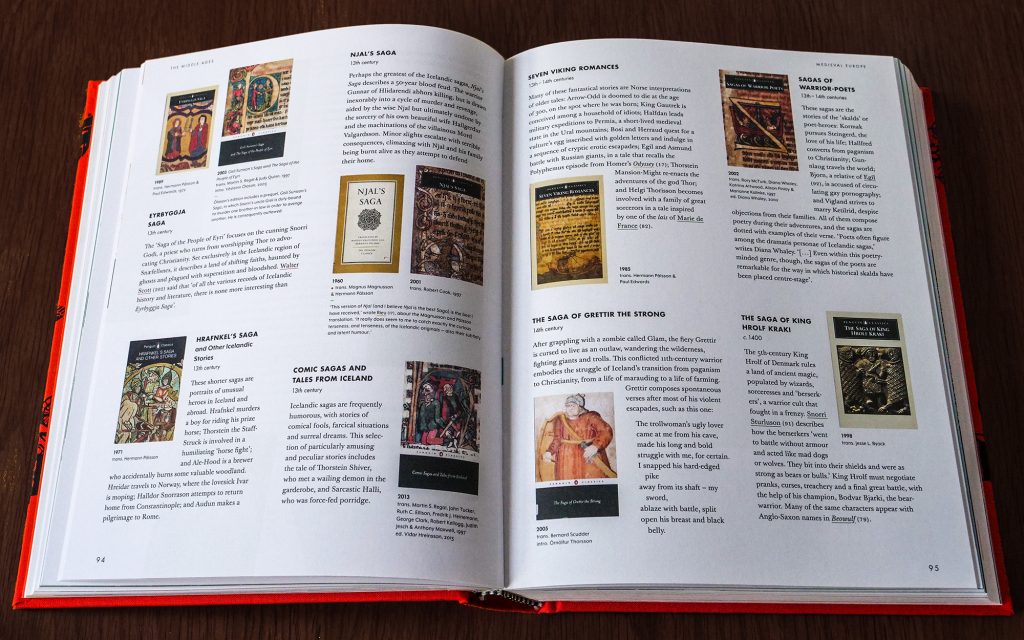

When I joined Penguin Classics, I was struck by the size of the series, and wanted to help readers navigate the list. The idea for The Penguin Classics Book grew out of this: it’s a companion for readers who want to explore the literary landscape. Readers can hone in on places they know, and get whisked off to places that might surprise them. Part of the pleasure of reading widely, is to see how literature is an ongoing conversation between writers.

The book is filled with illuminating descriptions of the titles in the series. How did you bring it all together?

In a way, writing The Penguin Classics Book was an unusual process. It covers such a vast period of literary history, yet the pieces for each title are relatively short. Rather than settling in for a marathon run, it felt like lots of little sprints.

For each description, I looked for something surprising and irresistible: a hook that would catch people’s attention. My primary source was the relevant Penguin Classics edition, the blurb, the introduction, and the text itself. Sometimes I needed to do more digging, and consulted reference books, including The Oxford Companion to English Literature. If I really drew a blank, I dived into the internet, and went down rabbit holes until I found a lead.

Surprisingly, it was the books that I knew well, that I found the hardest to write about. Authors such as William Blake and Jane Austen were particularly challenging, because there was so much I wanted to include. On the other hand, works that I was ignorant about beforehand, such as the Tibetan Buddhist texts on the list, were filled with brilliant material. I found these fantastic hooks, and the section came together very quickly.

With more than 4,000 years of literary history to include in The Penguin Classics Book, did any unexpected discoveries occur during your research?

As my research progressed, I discovered that a number of authors died in unusual ways. Robert Louis Stevenson apparently died of a brain aneurism while mixing up a batch of mayonnaise, and Aeschylus was killed by a tortoise, which was dropped by a passing eagle. One of the most surprising cases is the death of the Polish writer Jan Potocki, the author of the 19th century work The Manuscript Found in Saragossa. Towards the end of his life, Potocki believed he was a werewolf, and killed himself with a silver bullet, made from the knob of his favourite sugar-bowl.

Did working on the book highlight any gaps in the Penguin Classics series?

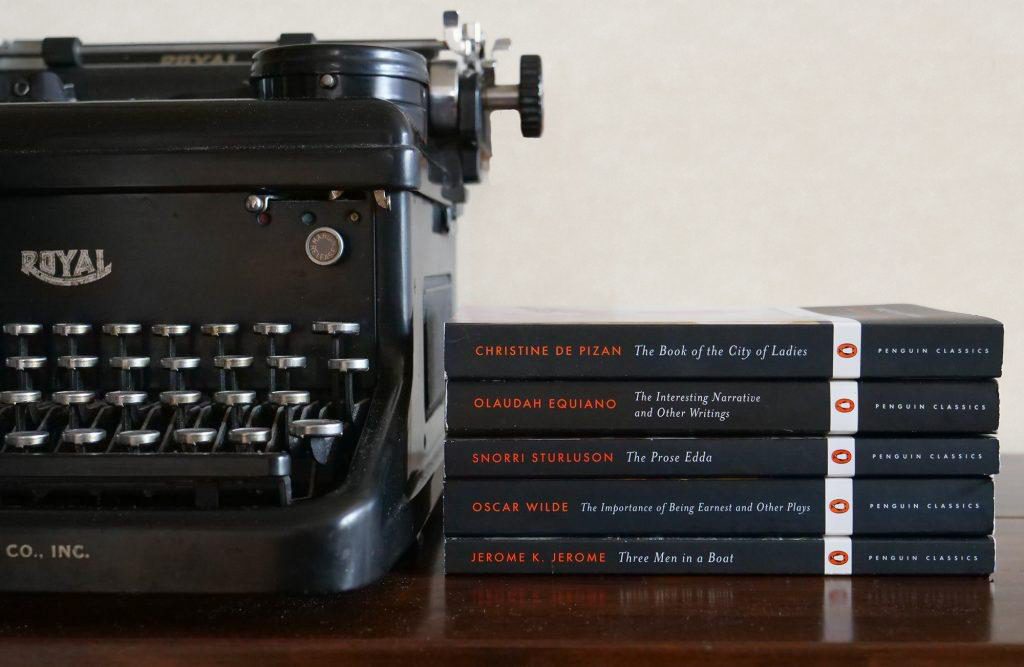

Since E.V.Rieu and Sir Allen Lane founded the Penguin Classics series in 1946, the list has grown idiosyncratically. But, there are areas that are under-represented: several works of Latin American and African literature are missing, and many works of women’s literature have been overlooked.

As Creative Editor, I’m responsible for looking at the list as a whole, from bringing new titles into the series to thinking about how people are engaging with it. There are lots of areas still to be explored. In 2019, we’re going to publish The Song of Kieu — the first Vietnamese classic in the series. Covering topics including jealous wives, slavery, war and poverty, this epic poem is a key part of the country’s cultural heritage. Yet, outside of Vietnam, it’s hardly known at all.

How do you commission new classics?

The process varies considerably. It may be that we need an edition of a certain title, in which case we explore the field, and find someone who we think is suitable. We have a network of previous editors and translators we can draw upon, who often come back to us with other ideas. We also receive direct proposals from translators and academics, and even suggestions from members of the public.

In addition to this, we gather focus groups to look at specific aspects of the list. We’re about to have an Arabic literature lunch, where we will bring together academics, translators, journalists and other experts, to advise us on what we could publish next.

Looking ahead, which direction would you like the series to take?

In order to remain relevant and exciting, the series has to stay alive — it needs to be thought about and refreshed. I like to think of it as this clear water lake in the mountains: it looks unruffled and still, but is continually fed and drained, which keeps it clear and healthy.

Over the past few decades, the Penguin brand has spread worldwide: there are offices in countries including India and Brazil, which create Penguin Classics in the same format. Currently, the offices are producing these titles reasonably independently, but I’d love to see that enterprise brought together, to make the series more global and agile. The logistics may be impossible, but it would be exciting!

Henry Eliot is Creative Editor of Penguin Classics. The Penguin Classics Book is published by Particular Books.

Image: © Georgie Gould